Many programmes remain too generic and short term to deliver lasting impact: Lecturer

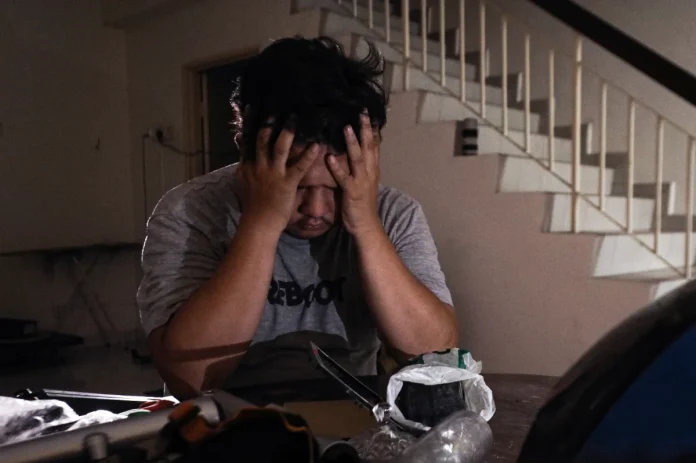

PETALING JAYA: Despite a surge of government-led initiatives in recent years, Malaysia’s mental health crisis is worsening, with fresh police data showing that more than 80% of the 5,857 suicide cases recorded between 2020 and October this year involved men, including 1,813 in the 15-30 age bracket.

Selangor recorded the highest number of cases, followed by Johor, Kuala Lumpur and Penang.

Against this backdrop, experts say the nation’s approach remains too reactive, focusing on crisis intervention rather than prevention, community support or healthier environments that protect people before they reach breaking point.

Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia senior lecturer and licensed counsellor Dr Farhana Sabri said different age groups require individually tailored interventions, yet many programmes are too generic and short-term to deliver lasting impact.

She said for children, long-term, skills-based learning, including mindfulness, anger management and grounding techniques, is far more effective than “one-off, feel-good” motivational sessions.

“Mental health support must be integrated into daily learning.”

She added that working adults need healthier workplace ecosystems.

While many companies run self-care workshops, recent findings published in the Cureus Journal this year show that these have little effect if employers ignore workload, team dynamics and managerial practices.

“Wellbeing depends on how work is organised. It is an organisational responsibility, not just an individual one.”

On Wednesday, Youth and Sports Minister Hannah Yeoh warned that the actual scale of the problem may be far higher due to underreporting and the fear of stigma, particularly in universities and workplaces where young adults risk being labelled.

“This is not a joke. It is a matter of life and death,” she said, calling for wider training for employers and educators.

Farhana said for older Malaysians, reducing loneliness and restoring purpose are key.

Structured community programmes that combine social groups, cognitive activities and light exercise have shown significantly better outcomes compared with casual gatherings, she added.

The World Health Organisation has similarly identified meaningful social roles, such as volunteering and intergenerational involvement, as strong protective factors.

“We cannot assume family support is enough. We need community hubs, such as surau, balai raya and resident associations, to keep seniors connected,” said Farhana.

She noted that while the National Strategic Plan for Mental Health 2020–2025 calls for community-led care and multi-agency collaboration, substantial gaps remain between policy and real-world practice.

Most resources revolve around hospitals, activated only when someone reaches a crisis point.

Meanwhile, root causes, such as bullying, domestic violence, workplace harassment and school absenteeism, continue to be addressed in silos despite clear links to mental distress.

“We are responding after harm has happened. Prevention is still underdeveloped and underfunded.”

Farhana said although the Health Ministry has introduced “quick guides” and early intervention protocols, their effectiveness hinges on proper training and leadership support.

“A guide may teach a teacher how to ask about mood, but not how to be empathetic if the culture still prioritises grades over wellbeing.”

She warned that without follow-up or reduced workloads, such tools risk becoming “just another document in a filing cabinet”.

Digital mental health tools, including telehealth, online counselling and AI-assisted apps, have widened access, especially between therapy sessions.

However, she cautioned against relying on them without proper regulation.

“Digital tools must exist within a regulated, stepped-care system. They cannot assess suicide risk or provide trauma care.”

Farhana stressed that mental health must be seen as a shared societal responsibility.

“When a child struggles, look beyond their ‘resilience’ to family and school pressures. When adults burn out, question workloads and bullying instead of telling them to ‘self-care harder’. When elders feel invisible, ask what it says about how we build neighbourhoods.”

Simple gestures, such as a teacher checking in on a withdrawn student, a supervisor normalising mental health days or a neighbour inviting an elderly resident to weekly activities, could be lifesaving, she said.

“Compassionate communities save lives. Each of us is part of the prevention network.”