WE refer to the article “Unaffordable” published in theSun July 4. Housing (un)affordability is often attributed to the high house price-to-income ratio, where house prices in the market increase rapidly leading to a huge disparity between household income and house prices.

With a ratio of 4.72 in 2020 – derived from the median household income of RM5,209 and the median house price of RM295,000 – the country’s house prices fall under the category of “seriously unaffordable” as indicated by the Median Multiple approach; hence, building more affordable houses to meet the demand of mass buyers is necessary to help improve the country’s housing affordability level.

At first glance, increasing the supply of affordable houses seems to be a viable measure not only to reduce the mismatch of housing supply and demand in the market, but also to improve homeownership rate among low-income groups, especially in areas with rapidly rising housing costs.

But this would not, by itself, make a significant dent in the country’s housing unaffordability problems.

In part that is because housing affordability is not just a problem facing low-income groups, but is likely to happen in every income group regardless of whether they are rich or poor.

Especially under the current economic front which is prevalent, with rising inflationary pressure and soaring material prices, the main contributing factor for housing unaffordability is more of the dampened household income and rising cost of living.

In fact, with 29% or 10,158 overhang units, 41% or 25,952 unsold units under construction and 42% or 10,046 unsold units not constructed yet that are derived from houses priced below RM300,000 as of first quarter of 2022 (1Q’2022), it is obvious that people lack discretionary income to afford what is on the market.

Under the circumstances that households are generally short of cash and may even need to make unrealistic compromises in other areas of their life if they are intending to commit themselves to servicing any housing loan coupled with the raising of interest rates announced by Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) recently, soaring borrowing costs mean the once so called “affordable houses” are no longer “affordable” to the mass people at present.

Therefore, today’s housing unaffordability is an economic issue that is deeply related to the country’s weak economic performance, rather than the mismatch of housing product and pricing in the market.

Furthermore, there is actually no shortage of affordable housing in much of the country.

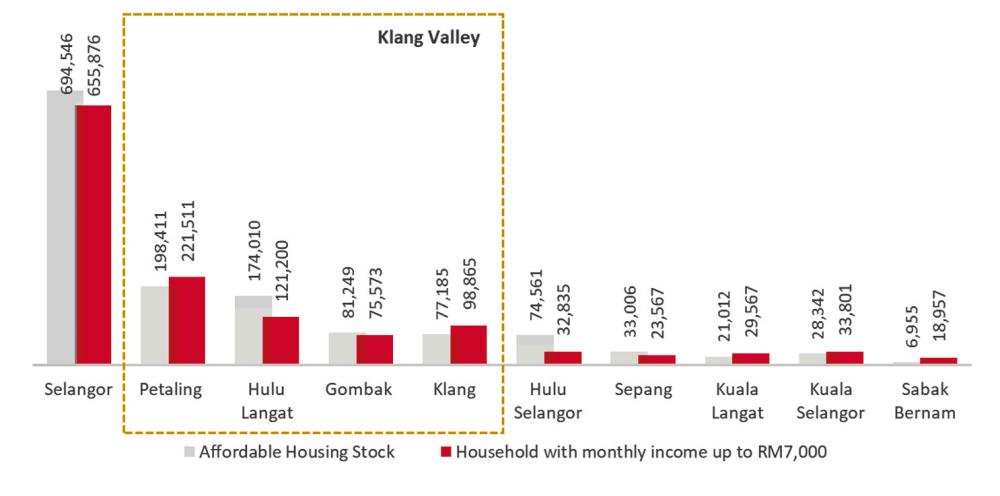

For example, by comparing the existing housing stocks (representing the supply side) with the total number of households (representing the demand side) in the state, Rehda Selangor shows that there is no shortage of affordable houses in Selangor, with the state being the most highly urbanised in Malaysia.

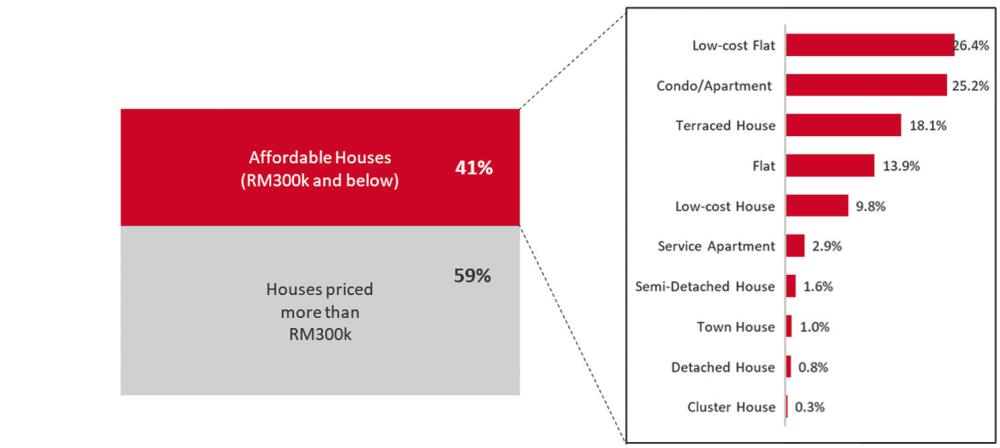

As of 4Q’2020, the existing stock of houses (including service apartments) in Selangor amounted to 1,683,147 units, 41% of them or 694,836 units were priced RM300,000 and below, which can be considered “affordable houses” that meet BNM’s definition.

These “affordable houses” are basically coming from a wide range of product categories, ranging from low-cost flat (26.4%), condominiums or apartments (25.2%), terraced houses (18.1%), flat (13.9%), low-cost house (9.8%), serviced apartments (2.9%) etc, see Figure 1.

If we were to compare the stock of houses below the price of RM300,000 against the number of households that are financially eligible to purchase a property priced up to RM300,000, it is found that the state has, in fact, sufficient affordable houses to cater for the targeted households: 694,546 houses against 655,876 households, see Figure 2.

Supply of affordable houses in most districts are found exceeding demand (number of households), including those that are located within the Klang Valley region.

Most importantly, do not forget that there are affordable houses under construction and in the planning stage.

As long as the rate of supply outpaces the rate of demand, there should be no shortage of affordable houses across the state.

Instead, what should be concerning the most is the overbuilding of price-controlled affordable houses, with high unsold units, low take-up rate and low marketability.

Recent statistics released by the Department of Statistics Malaysia revealed that living quarters in Malaysia amounted to 9.6 million in 2020, compared with the number of households that reached 8.2 million.

Of this number, about 1.9 million or 19.4% of the living quarters are vacant.

In the case of Selangor, there are 2,101,896 living quarters against 1,836,410 households, and as high as 343,562 living quarters or 16.3% are vacant.

The highest percentage of vacant living quarters at the administrative district level due to newly completed or for rent or sale is in Sepang (71.3%), Gombak (62.9%), and Petaling (62.9%).

Suppose the main driver of the problem is the badly impaired people’s purchasing power, building more price-controlled affordable houses (like PR1MA, RSKU) that aim to increase the low-income group’s homeownership will never be able to enhance people’s housing affordability as we will eventually end up in a situation of whether it is possible to build housing cheap enough to make it affordable to the low-income group.

Moreover, experiences from the existing price-controlled affordable housing schemes like PR1MA and RSKU have shown that the construction of these houses is only viable through cross-subsidisation from other housing products targeted for different income groups, which not only contributes towards a skewed-market that is in favour of launching high-end products, but also tends to exacerbate the problem of oversupply in the affordable housing market segment.

The government should realise that when wages and salaries are not catching up with the prices of commodities that are continually increasing, housing affordability level is inevitably decreased.

To opt for a long-term solution to tackle housing unaffordability, the government should move away from the approach that is simply aimed at building more affordable houses to emphasising on ways to stimulate more job creation, income growth, as well as helping industries and businesses to survive, grow and transform, which are all key drivers to spur the country’s economy.

To complete the picture in solving the problem, measures should not only be limited to financial support given to buyers but also to include ways to incentivise builders in supplying houses, such as facilitating the improvement in cost, productivity and process efficiency, providing incentives for technology transformation as well as enhancing the ability of the housing market in addressing the dynamic and growing demand through data accessibility and transparency.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is Principal Research of MKH Berhad and James Tan Kok Kiat is Suntrack Development Sdn Bhd CEO. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com