Myanmar’s military holds a heavily restricted election, widely condemned as a sham, with no voting in rebel-held areas and Aung San Suu Kyi’s party excluded

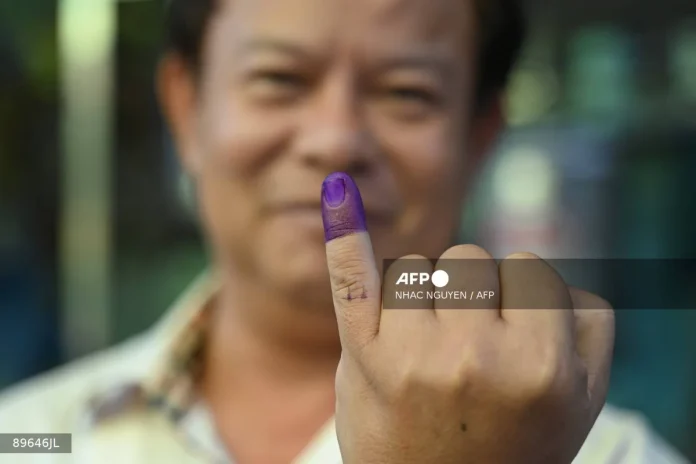

YANGON: A trickle of voters made their way to Myanmar’s heavily restricted polls, with the ruling junta touting the exercise as a return to democracy five years after it ousted the last elected government.

Former civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi remains jailed, while her hugely popular party has been dissolved and is not taking part.

Campaigners, Western diplomats and the UN’s rights chief have all condemned the phased month-long vote, citing a ballot stacked with military allies.

The pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party is widely expected to emerge as the largest bloc.

“We guarantee it to be a free and fair election,” junta chief Min Aung Hlaing told reporters in the capital Naypyidaw.

“It’s organised by the military, we can’t let our name be tarnished.”

The Southeast Asian nation of around 50 million is riven by civil war.

There will be no voting in areas controlled by rebel factions which have risen up to challenge military rule.

Journalists and polling staff outnumbered early voters at a downtown Yangon station near the gleaming Sule Pagoda.

Among a trickle of early voters, 45-year-old Swe Maw dismissed international criticism.

“It’s not an important matter,” he said. “There are always people who like and dislike.”

At another polling station near Aung San Suu Kyi’s vacant home, the first voter said the election was “very important”.

“The first priority should be restoring a safe and peaceful situation,” the 63-year-old told AFP.

In total only around 100 people voted at the two stations during their first hour of operation, according to an AFP tally.

The run-up saw none of the feverish public rallies that Aung San Suu Kyi once commanded.

“I don’t think this election will change or improve the political situation in this country,” said 23-year-old Hman Thit, displaced by the post-coup conflict.

“I think the airstrikes and atrocities on our hometowns will continue even after the election,” he said in a rebel-held area.

The military ruled Myanmar for most of its post-independence history, before a 10-year interlude saw a civilian government take the reins.

After Aung San Suu Kyi’s party trounced pro-military opponents in the 2020 elections, Min Aung Hlaing snatched power in a coup, alleging widespread voter fraud.

While the military put down pro-democracy protests, many activists quit the cities to fight as guerrillas alongside ethnic minority armies.

Meanwhile Aung San Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence for charges rights groups dismiss as politically motivated.

“I don’t think she would consider these elections to be meaningful in any way,” her son Kim Aris said from his home in Britain.

Most parties from the 2020 vote, including Aung San Suu Kyi’s, have since been dissolved.

The Asian Network for Free Elections says 90% of the seats in the last elections went to organisations that do not appear on Sunday’s ballots.

New electronic voting machines will not allow write-in candidates or spoiled ballots.

The junta is pursuing prosecutions against more than 200 people for violating draconian legislation forbidding “disruption” of the poll.

“These elections are clearly taking place in an environment of violence and repression,” UN rights chief Volker Turk said last week.

The second round of polling will take place in two weeks before the third and final round on January 25.

The junta has conceded elections cannot happen in almost one in five lower house constituencies.