OXFORD recently announced “rage bait” as its Word of the Year for 2025. The term refers to digital content created purposefully with the aim of triggering anger and annoyance in users.

The content itself can be inflammatory or provocative, as it commonly relies on emotional cues designed to capture attention.

Rage bait is commonly used in marketing advertisements to promote products or personal accounts. In Malaysia, for instance, audiences have come across videos showing someone offering a homeless man a package of chicken bones and rice with the intent to drive traffic to their account, and another depicting a couple “arguing” in a grocery store, which turned out to be a marketing stunt.

These examples may appear ordinary but they are designed to make viewers react and engage. The purpose is to farm engagement and increase viewership by amplifying discourse surrounding the content.

Apart from being a marketing tactic used to promote a specific message, rage bait is also a linguistic phenomenon that affects the digital environment. The way messages are phrased, including their wording, framing and tone, can trigger certain groups of people. As a result, content can pull users into cycles of hostility or emotional overload.

Rage baiting is commonly used by media outlets through sensationalised headlines designed to hook readers emotionally.

In some cases, the headline does not reflect the actual content of the news, creating a misleading first impression. Users who scroll through and read only the headlines can therefore be easily misled by this strategy. This subsequently creates another cycle of outrage and misinformation.

In such situations, readers commonly respond to a simplified or exaggerated version of the issue rather than the full context. Their understanding is shaped by partial information. This, in turn, limits their ability to make an informed judgement or to interpret the issue accurately and fairly.

As this becomes normalised, different groups begin to rely on headline-level narratives that reinforce existing biases, which in turn leads to people understanding issues differently across communities.

People tend to understand issues differently when they overlook nuances when discussing complex topics such as policy, social issues or cultural debates. This can further promote discourse that is reactive rather than reflective.

Consequently, informed engagement becomes more difficult and reactive tendencies remain deeply entrenched in interactions in online spaces.

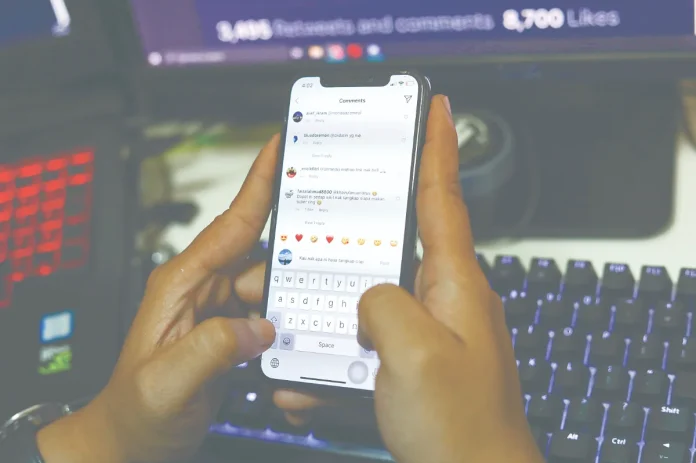

Studies have shown that outrage-driven reactions are rewarded with likes and shares, which are then amplified by algorithmic visibility. This pushes content creators to produce what performs well and engages the audience rather than what informs.

To make matters worse, the combination of anonymity and high visibility afforded by online platforms reduces accountability.

More importantly, rage baiting can also affect users’ well-being. Constant encounters with anger-inducing headlines and hostile comment sections can heighten stress and make online spaces feel emotionally draining. Over time, this exposure desensitises users to conflict while normalising adversarial communication.

Not surprisingly, internet users tend to forget that their writing is being read by actual human beings. This cycle, if left unaddressed, has a range of implications that affect digital behaviour, public understanding and social interaction. Breaking the cycle, therefore, requires targeted effort.

So, what do internet users need to do when they log into the digital world? First, they must approach digital content with awareness rather than impulse. This means reading beyond headlines, seeking context and verifying information before reacting or sharing, especially when the content appears intentionally provocative.

Second, users should be mindful when communicating online by remembering that comments are (whether intentional or not) directed at real people with emotions and identities. This awareness will help reduce unnecessary hostility and encourage civil exchanges. Mindfulness also promotes the habit of pausing before responding, which can change the tone of online interactions.

Third, users need to consciously cultivate digital literacy. This includes understanding how algorithms amplify certain content and recognising linguistic cues of rage bait, which allow users to navigate online spaces more calmly.

Additionally, awareness of how content is prioritised will help users avoid being manipulated by sensationalism. Recognising emotional cues can also train users to differentiate between information and provocation.

Fourth, users can benefit from setting boundaries around their digital consumption. Curating their feed, taking breaks or choosing sources that prioritise accuracy over dramatisation can improve their online experience. These small adjustments can help protect their emotional well-being in the long run.

Finally, fostering empathy in digital interactions can promote civil exchanges. Empathy shifts online culture away from hostility and towards reflective engagement. The world is shaped by how we interact with each other.

Dr Najah Zainal Abidin is a senior lecturer in linguistics at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, Universiti Malaya. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com