WE live in an age of jarring contradictions. The United States, a nation literally forged by immigrants – from the Mayflower to Ellis Island and Silicon Valley – now grapples with fierce political movements demanding walls and closed borders.

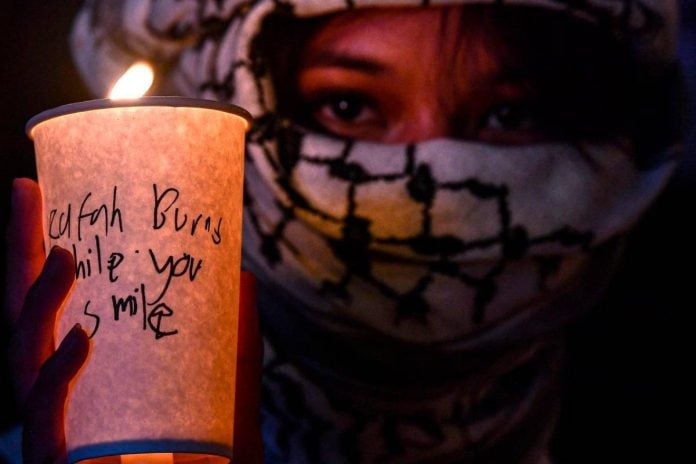

Meanwhile, halfway across the world, the modern state of Israel, established as a homeland for a persecuted diaspora, now pursues policies many see as systematically displacing the Palestinian people whose ancestors lived on that same land for centuries. It feels like historical whiplash, a collective madness. What drives this seeming global schizophrenia?

The uncomfortable answer lies not in inherent craziness but in the collision of deep-seated human anxieties, historical trauma and the brutal calculus of power when resources feel finite and identities feel threatened. Both situations expose a painful psychological transition.

Societies built by immigrants or refugees eventually reach a point where they become the established group. The very openness that allowed their creation becomes perceived as a threat to their hard-won security, culture and economic stability.

The US, after waves of immigration, now sees segments of its population fearing cultural dilution, job competition and strained social services. Israel, born from the ashes of the Holocaust and centuries of displacement, achieved statehood but now faces demographic pressures and security threats from the Palestinians it displaced or incorporated.

The trauma of being the outsider can morph into a fierce determination to never be vulnerable again, often expressed by controlling who is now considered the outsider.

National identities are often built on powerful, sometimes simplified, narratives. The US mythos celebrates the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” but often glosses over the displacement of native Americans and the exploitation of immigrant labour.

Israel’s founding narrative centres on “a land without a people for a people without a land”, which inherently dismisses the centuries-long Palestinian presence.

When the lived reality – ongoing indigenous claims, the presence of “other” peoples with deep roots and the complexities of integration – persistently challenges the foundational myth, the response isn’t always reconciliation; it can be denial, defensiveness and a hardening of borders, both physical and psychological. Protecting the myth feels like protecting the nation itself.

At the heart of both scenarios lies a potent fear: the fear of being overwhelmed, replaced or losing control. In the US, this manifests as anxieties about changing demographics, cultural shifts and economic competition.

In Israel-Palestine, it is the zero-sum demographic struggle over land and political control between the river and the sea. When resources (land, water, jobs and political power) are perceived as limited or when identity feels intrinsically tied to maintaining a demographic majority, empathy erodes.

The “other” transforms from neighbour or potential citizen into an existential threat. Logic and historical context become casualties in the struggle for perceived survival.

Past suffering can be a powerful motivator for building safe havens but it can also be weaponised to justify inflicting suffering on others.

The profound historical trauma of Jewish persecution fuels Israel’s determination for security, sometimes leading to policies that inflict trauma on Palestinians.

Similarly, descendants of immigrants who faced hardship can sometimes develop a stance of “we made it, now pull up the ladder”, forgetting their own ancestors’ struggles. Unprocessed trauma, coupled with power, can create cycles of violence and exclusion, each side feeling justified by past wounds.

Is it “crazy”? Or predictably human? Labelling it “crazy” absolves us of the harder analysis. This isn’t irrationality in a vacuum; it is a tragic, recurring pattern in human history.

Groups achieve safety or dominance and then pull up the drawbridge. Trauma hardens into defensiveness. Myths ossify and resist inconvenient truths. Fear of the “other” trumps empathy, especially when resources feel scarce and identities feel fragile.

Breaking this cycle requires a conscious effort that runs counter to base instincts: nations must confront the complexities and injustices within their founding narratives, not just the heroic parts.

Systems must be built that recognise the dignity and rights of all people within a territory, moving beyond exclusive ethno-nationalism. Security concerns and economic anxieties need solutions that don’t demonise entire groups.

We need leaders who foster empathy and envision shared futures, not those who stoke fear and division for political gain.

The world isn’t growing “crazy”; it is revealing a deeply ingrained human vulnerability: the struggle to transition from the persecuted outsider to the secure insider without replicating the exclusion that once harmed us.

Recognising this pattern is the first step towards breaking it. The alternative is a future defined by ever-higher walls and deeper cycles of resentment – a madness from which we may never awaken.

By Prof Datuk Dr Ahmad Ibrahim is affiliated with the Tan Sri Omar Centre for STI Policy Studies at UCSI University and is an associate fellow at the Ungku Aziz Centre for Development Studies, Universiti Malaya. Comments: [email protected]