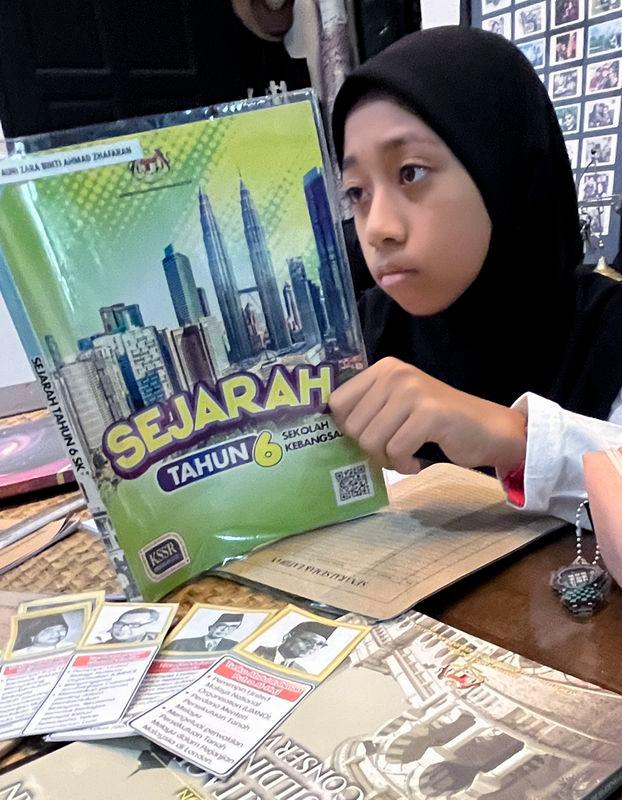

PETALING JAYA: A growing call to revise Malaysia’s primary school history textbooks is gaining traction, with educators and parents urging a more inclusive approach to the nation’s past.

Parent Action Group for Education president Datin Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim voiced strong support for curriculum reforms, emphasising that revisions should be guided by textbooks from the 1980s, which she described as free from political influence.

“Parents will welcome these changes, but they must be rooted in historical accuracy,” she said.

She added that the current textbooks place disproportionate emphasis on the history of Malacca, while neglecting the roles of Sabah and Sarawak.

“There should be a deeper understanding of East Malaysia’s contributions to nation-building. The experiences of Sabahans and Sarawakians must not be sidelined,” she told theSun.

Noor Azimah also said the late historian Prof Emeritus Tan Sri Khoo Kay Kim had previously been consulted by the Education Ministry to review the syllabus, but his recommendations were shelved.

She urged officials to reconsider his findings and approach history with an open mind.

“The ministry should revisit his work, accept history as it is, and ensure that it remains free from bias.

“If mistakes were made in the past, acknowledge them, learn from them, and move forward.”

Concerns over the lack of representation of Malaysia’s diverse ethnic groups in historical narratives had long simmered.

Educationist Tan Sri Dr T. Marimuthu stressed that a more accurate portrayal of history is critical for fostering national unity.

On Feb 24, Kota Melaka MP Khoo Poay Tiong called on the government to revise primary school history textbooks to better reflect the contributions of all ethnic groups.

He had pointed to significant omissions, such as the historical connections between Laksamana Cheng Ho and Malacca.

Education Minister Fadhlina Sidek acknowledged the concerns, stating that a special committee comprising historians, experts, and teachers is responsible for determining the content taught at various schooling levels.

Marimuthu underscored the need to recognise the role of non-Malays in shaping the nation, arguing that their presence in Malaysia was deeply tied to colonial history.

“It is a mistake to overlook the contributions of Indians, Chinese, Christians, and others.

“Why are they here? When did they come? These are questions that must be addressed.”

During the British colonial era, Indians were brought in to develop plantations, construct railways, and clear dense jungles, while Chinese immigrants played a major role in the tin mining industry, he said.

Many ultimately settled in Malaysia, shaped by historical events such as World War II, creating the multicultural society seen today.

For Marimuthu, teaching students about the struggles and sacrifices of different communities is not divisive – it is essential for building informed citizens.

“If students only learn one side of history, how can they truly understand their country?”

Despite concerns that expanding historical narratives might face resistance, Marimuthu dismissed the notion that inclusivity is controversial.

“There are no challenges. This is knowledge.

“This is historical fact. You don’t rewrite history to favour one group,” he said.

Calling for a more balanced curriculum, he urged the Education Ministry to include historians from diverse backgrounds in the review process.

“Historical facts are not controversial. Children must grow up with the truth,” he said.

As Malaysia re-evaluates how it teaches its history, Marimuthu and other advocates are pressing for an educational framework that acknowledges the nation’s rich multicultural heritage.

“We are simply repairing what is incomplete,” Marimuthu said.