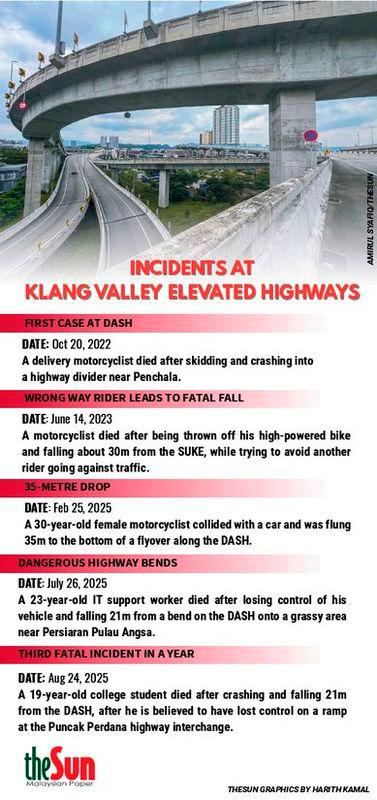

PETALING JAYA: The recent death of a motorcyclist on the Damansara–Shah Alam Elevated Expressway (DASH) has rekindled concerns over the safety of elevated highways, following three fatal crashes recorded on the route this year alone.

Road safety experts have said the design of elevated highways makes crashes deadlier than those on ground-level roads, with motorcyclists facing the greatest risks.

Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) Road Safety Research Centre head Assoc Prof Dr Law Teik Hua described three fatalities in a year as “an alarming number that warrants urgent attention.”

“A (crash) on an (elevated) highway is more dangerous than on a flat road, particularly for motorcyclists. The main reason for the high mortality rate is the height and structure of the bridge. It is nearly impossible to survive a fall from 21m,” he told theSun.

Law said the curves and ramps on an elevated highway demand full attention from motorcyclists, while speeding, fog, pooled rainwater and glare further increase risks.

On Aug 24, a private college student died after losing control of his motorcycle at the Puncak Perdana interchange and plunging 21m from DASH.

Highway concessionaire Prolintas, which operates the expressway, said the it complies with all design standards, adding that extra warning signs, public awareness campaigns and additional fencing are being planned.

However, Law said such steps may not be sufficient.

“Awareness and signage depend on flawless rider behaviour, which is not realistic. The real issue is the unforgiving design, in which any error near a low barrier is fatal. A proper solution requires physical changes, not just warnings.”

He recommended stronger and higher concrete dividers, improved surface grip, larger LED warning signs and even safety nets at high-risk stretches.

“Authorities often focus on rider behaviour, but repeated fatalities suggest design issues must also be addressed.”

UPM Civil Engineering Department head Assoc Prof Dr Fauzan Mohd Jakarni said while DASH meets technical standards, those standards do not fully reflect the realities faced by motorcyclists.

“Most standards were written with cars and heavy vehicles in mind. A car hitting a barrier usually stops on impact, but for a motorcyclist, the barrier may not be high enough to prevent a fall. It is like a cup filled to the brim, even a small jolt spills water over the edge.”

Fauzan said elevated highways magnify risks due to wind, speed and the absence of escape lanes.

“Their smooth design tempts drivers to go faster, but speed magnifies every risk. On elevated roads, once a mistake happens, recovery is almost impossible.”

While retrofitting safety nets or roller barriers may be costly, he urged targeted safety audits to pinpoint crash-prone sections.

“On paper, DASH complies fully with standards, but the number of motorcycle fatalities shows that technical standards alone are not enough. Identifying ‘black spots’ and applying targeted solutions such as rumble strips, wind barriers or speed-calming measures could save lives.”

He also said safety relies on responsible behaviour.

“Engineering could reduce risks, but if riders speed recklessly or drivers fail to respect motorcyclists, (crashes) would continue. Malaysia may need to update its highway design guidelines while also tackling the human side by encouraging riders to slow down and all road users to treat elevated highways with caution.”

Fauzan said a two-pronged approach is needed, with operators enhancing infrastructure and riders committing to safer behaviour.