Outdated fundraising laws leave loopholes that enable misuse of public donations, hamper oversight and accountability on digital platforms: Experts

PETALING JAYA: Malaysia urgently needs a dedicated legal framework to regulate donation-based online crowdfunding, said experts, as outdated laws leave loopholes that allow the misuse of public donations on digital platforms.

The call comes in the wake of remarks by Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Chief Commissioner Tan Sri Azam Baki, who told a Malay daily last week that the absence of specific crowdfunding legislation has enabled unscrupulous parties to exploit public generosity, particularly via social media.

Transparency International Malaysia (TI-M) president Raymon Ram said Malaysia currently has no law specifically governing donation-based online crowdfunding, leaving enforcement agencies struggling to act proactively.

“Existing legislation, such as the House-to-House and Street Collections Act 1947, was designed for physical fundraising and does not cover digital platforms.

“As a result, individuals, influencers or loosely organised groups can solicit public donations online without prior approval, licensing or real-time oversight.”

Raymon added that while registered NGOs must comply with annual reporting requirements under the Registrar of Societies, there are no specific controls for online fundraising, including how funds are ring-fenced, monitored or accounted for during and after campaigns.

“This leaves enforcement agencies operating reactively, often intervening only after funds have been misused – an approach that is neither efficient nor adequate to protect public generosity,” he said, stressing the need for a preventive regulatory model.

“Online donation solicitations must be explicitly recognised as a regulated activity, supported by mandatory registration or prior approval.”

He said crowdfunding platforms themselves must also be held accountable.

“Platforms should be licensed and subject to clear obligations to conduct due diligence, verify claims, safeguard funds and ensure transparency through proper disclosures and audit trails,” Raymon said.

The absence of a dedicated Charities Act further weakens oversight, he said, pointing out that Malaysia’s charitable sector is governed by a fragmented framework involving the Societies Act 1966, Trustees (Incorporation) Act 1952, Companies Act 2016 and outdated fundraising laws.

“Unlike in jurisdictions such as Singapore and the United Kingdom, Malaysia does not have a single charity regulator with the mandate to license public fundraising, monitor donation flows or intervene early to prevent abuse.

“Malaysians are generous by nature. That generosity must be protected by law, not exploited by regulatory gaps,” he said.

From a digital law perspective, International Islamic University Malaysia deputy legal adviser Assoc Prof Dr Sonny Zulhuda said donation-based crowdfunding must be conducted ethically, transparently and accountably.

“There is a legitimate expectation from funders that donated funds will be channelled strictly towards their stated purposes and not abused or misused.”

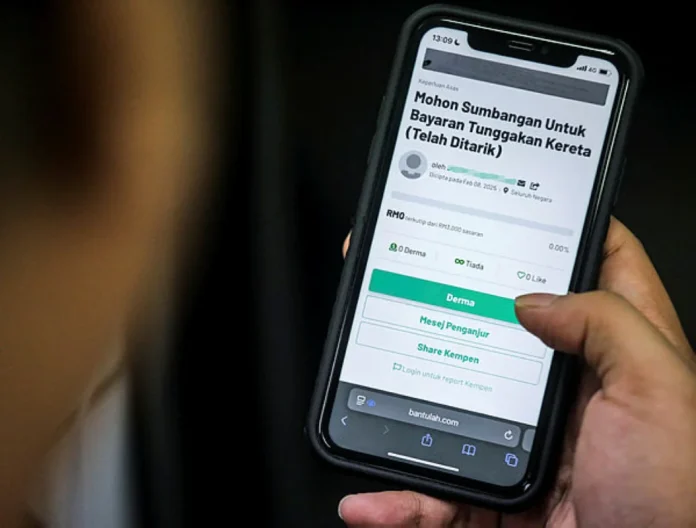

Sonny said crowdfunding initiatives should preferably be conducted through recognised online platforms, rather than informal or ad-hoc methods such as direct messaging.

“An online platform – whether a website, social media page or application – provides the necessary infrastructure for accountability and governance.”

Such platforms, he added, allow for minimum regulatory or self-regulatory mechanisms, including disclosure of fundraising purposes, organiser identity and beneficiaries, as well as clear terms and conditions and transparent payment systems.

“They also enable proper record-keeping for fund traceability, personal data protection safeguards and accessible channels for inquiries or complaints.”