PENANG: “Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue” may seem like a Western tradition for brides, but for the Straits Chinese in Penang, particularly those of Hokkien descent, the Baba and Nyonya community is exactly the epitome of that phrase .

Much like the cherished bridal tradition, the Baba and Nyonya culture intertwines elements of “something old” – rooted in the 15th century arrival of Chinese settlers adopting local indigenous customs – with “something new,” representing the evolving practices and customs that have shaped their unique identity over the centuries.

This cultural montage also borrows influences from the Malays, creating a harmonious blend akin to “something borrowed.” As for “something blue,” it resonates with a sense of connection, reflecting the maritime trade roots integral to their heritage, and perhaps, subtly alluding to British influence, whose eyes were often blue, and reminiscent of the being known as the “King’s “Chinese who speak the Queen’s English.”

According to historical records, Chinese maritime traders engaged in trade in the Malay Peninsula as early as 618AD during the Tang Dynasty, and these influences continue to permeate the Baba and Nyonya community in Penang today.

Broadly known as Peranakans, these Sino communities can be found in Kelantan, Terengganu, Malacca, Penang, Sabah and Penang. Detailed records are scanned prior to the 15th century, and the earliest known Chinese settlers in Southeast Asia were documented by Admiral Cheng Ho’s traveling companion and translator, Ma Huan, in the early 1400s. Other than that, it is believed Kublai Khan invaded Borneo in 1292 during the Yuan Dynasty and established a settlement along the Kinabatangan River.

Tian Chua, a former member of Parliament who identifies as a Baba from Malacca, asserted that the Straits Chinese adopted Malay culture to integrate with the local population, aligning with the historical context of the region. “They saw the Malay culture as being superior.”

The desire to distance themselves from certain practices in China, such as foot binding, further demonstrates the adaptive nature of the community. This cultural assimilation was not just a means of blending in but a true acceptance of local customs and traditions.

“At that time, Chinese women, including my grandmother, wanted to escape foot binding. We maintained the Chinese cultural aspects and incorporated aspects of the local community which seemed superior to the ‘backward’ mainlanders and new immigrants or Sinkhek .

“Baba and Nyonya are essentially Chinese people who embraced the Malayan socio-economic, and later political conditions,” he said. “Men typically wear suits and ties, reflective of the prevalent British influence in that era.”

Over at the Penang Peranakan Mansion on Church Street, visitors are seen exploring the property, capturing a glimpse into the lives led by the late Kapitan Chung Keng Kwee’s family – one of the wealthiest families in Penang in the late 19th century.

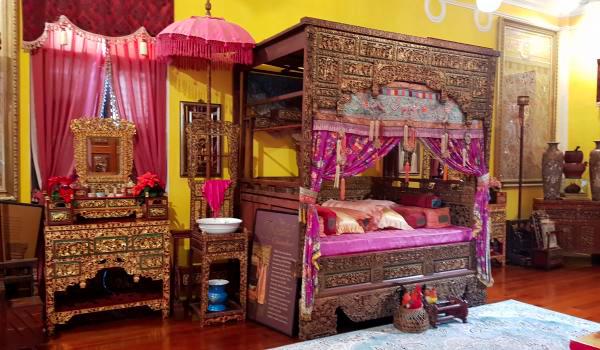

The mansion has intricately designed rooms, adorned with exquisite Baba and Nyonya artefacts preserved within its walls, including beautiful geometric tiles with symbolic motifs that spread across every inch of the indoor floor space.

However, in the inner courtyard where the air is well, the ground is covered with stone slabs.

“There are both Western and Chinese influences here. Besides the beautifully designed furniture, there are Eglomise, which are reverse-painted mirrors, and bell jars that were popular in the Victorian era. Tulips, which were prized as much as gold during that time were also appreciated, as were marble statues made of Carrara marble, the same marble that Michelangelo used for his statues,” said Datuk Lilian Tong, who is the president of the Persatuan Peranakan Baba Nyonya Pulau Pinang and the deputy president of the State Chinese (Penang) Association.

Tong, the founder of the Ronggeng dance troupe and author of five books on the Baba and Nyonya heritage, including Once Upon a Kamcheng , a collection of stories from the Baba and Nyonya community, recalls a time when Baba and Nyonya were often mocked and called names like orang Cina bukan Cina .

“Eventually, many Baba and Nyonya opted to register their children as Chinese on their birth certificates,” said the Nyonya. “We were mostly English-educated and communicated with a mix of Hokkien, English and Malay at home. Due to this, we were also sometimes called ‘bananas’, yellow on the outside and white on the inside. We are also slightly different from the Baba and Nyonya in Malacca in that sense. “There are families in Malacca who spoke mainly in Malay.”

The process of acculturation has played a significant role in the gradual disappearance of the distinct Baba Nyonya culture, blending it seamlessly into the identity of Penang’s Chinese community today. The eleven-distinctive elements of Baba Nyonya traditions, from the language spoken, Penang Hokkien, to the enjoyment of culinary delights such as chap chai, nasi lemak, otak-otak , and sweet treats like kuih kapit, kuih bakul and kuih bangkek are now synonymous with the broader Penang Chinese culture. As evidenced in the Malay names used, such food subtly hints at the unmistakable roots of the Baba and Nyonya heritage.

This blending is so pervasive that the unique origins of the Baba Nyonya heritage often fade into the background, making it an integral, albeit less distinguishable, part of the contemporary Penang Chinese identity. Interestingly, while Penang Hokkien differs from any Hokkien spoken in Malaysia or China, it shares close similarities with the Hokkien spoken in Medan, Indonesia, in terms of intonation.

Aunty Pat, an 81-year-old Nyonya who lives in Pulau Tikus, said: “We must keep evolving to keep up with the current trends. However, our core values must never change, and that is why mothers play an important role in educating their children.

“The Baba and Nyonya always put family first, then our neighbors and community come next. That is why education is always a priority, and many of us work in the public sector.”

Pat was given the name Patricia by the sister of the Convent Pulau Tikus (CPT). “I was the first batch at CPT, for the primary and secondary school and graduated with Senior Cambridge in 1959,” she recalled.

Although she now wears her hair short and no longer wears a sanguih , she still maintains the kebaya and muar or sarong as her daily attire. Sanguih is from the Malay word sangul .

In Penang, many Malay words are used, but with the many last letters being replaced by the letter “ i” or “ih”. Hence “mari” becomes “mai”, “aduh” becomes “adui” and “betul” becomes “betui”.

“Penang kebaya has the perfect cut or potong coat that follows the curve of the body,” Pat said.

“To know if a kebaya is made in Penang, just look at the underside of the cloth to see if both sides of the embroidered kerawang ‘ which is the lacework, look exactly the same.”

This needlework technique, known as tebuk lubang, involves sewing the outlines of a floral motif on the fabric and then cutting away the unused parts, leaving a meticulously crafted and symmetrical design.

“A fine piece of sarong will also have higher thread count, and this can be observed by the tell-tale signs at the edge of the sarong .”

The Penang Baba and Nyonya will be having two events on Nov 29 and 30 to celebrate the 103rd anniversary of the State Chinese (Penang) Association. For ticketing information, contact Lily Wong at 012-427 0678.