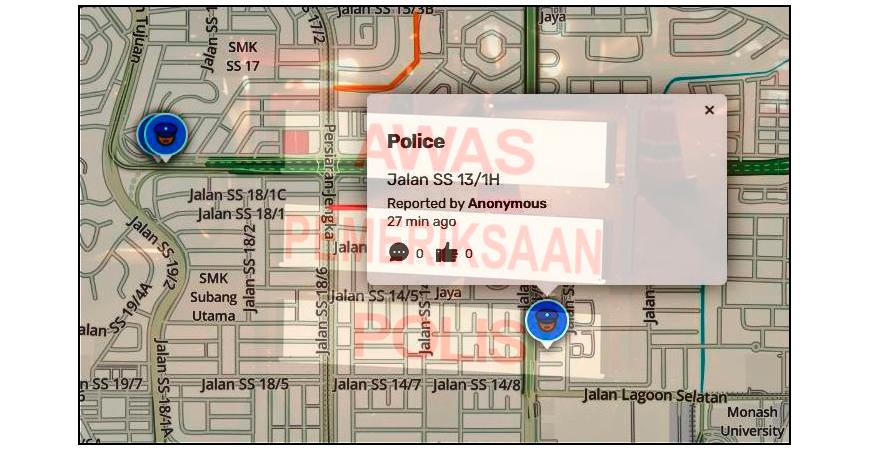

THE Malaysian police (PDRM) have asked the public not to share information on their operations relating to roadblocks to check motorists and vehicles. Such information is contributed by users of the Waze GPS route navigation app and alerts motorists to the presence of such operations on the road ahead of them.

Speaking at an event in Kuala Lumpur last night, Kuala Lumpur police chief Datuk Azmi Abu Kassim said such information will hamper enforcement efforts against motorists driving under the influence of alcohol (drunk drivers) and those who commit other traffic offences. When alerted, motorists who are aware that they can be caught for an offence may then avoid the roadblock.

Datuk Azmi is asking the public to cooperate with the police on this and not provide information that helps those who commit road offences. He said road-users should be aware of the dangers they face due to negligence from drunk drivers, those not stopping at red lights, driving against the flow of traffic and so on.

“Those who have never been affected by the misfortune caused by the carelessness and negligence of traffic offenders, will not be able to feel the pain and suffering victims’ families have to endure,” he said.

While there is no law in Malaysia which makes it an offence to report (on Waze) the presence of a police roadblock, there are some countries which have insisted that Waze remove the feature on its app. However, the police chief has a point that drivers who are drunk need to be stopped because they pose a danger to others on the road. They should therefore not be alerted so that they can immediately be caught and stopped from driving in that unsafe condition.

The act of drivers helping drivers to provide alerts of roadblocks and speedtraps is decades old, probably since speedtraps started in the 1970s. Those who travel along the highways will know that flashing headlights from vehicles on the other side mean that a speedtrap is up ahead. This made the police try their best to hide themselves when they ‘shot’ at speeding vehicles or to set up the detention roadblocks a greater distance away (from the speedtrap) so that they could fool motorists.

There have been occasions that police have threatened to take action against ‘flashers’, citing the action as ‘obstruction of police duty’. But it’s not easy to prove that the motorist was flashing his light to warn others. He might claim that he was flashing to alert the car ahead that he was overtaking, or he was ‘checking if the lights worked’.

Naturally the police hate it when motorists are warned and slow down to the speed limit before they pass the speedtrap. But a point that has been debated over the years has been the objective of the police action when they set speedtraps: is it to catch people who have committed an offence and collect fines, or is it to make motorists obey speed limits and therefore reduce accidents?

If awareness of a speedtrap ahead forces a motorist to reduce his speed from 160 km/h to the limit of 110 km/h, is that not already contributing to safety? Of course, we know that once past the speedtrap, many motorists will speed up and exceed the speed limit again. But speedtraps are set up in areas where there is a high risk of accidents, so making them lower their speed has already achieved the objective.

On the other hand, issuing a summons for a speeding offence would mean that they have been travelling at high speed – beyond the limit – all the way to the speedtrap, thus posing a risk to themselves and other road-users. How is that going to contribute to safer motoring, other than making the motorist pay a fine?

In Australia, there have been cases where motorists have protested against speedtraps at certain locations. They argued that those locations are not dangerous to warrant speedtraps and that the action is only for the police to collect money (for their operations, not themselves). However, the situation in some countries is different as police departments might not be fully funded by the central government (as in Malaysia), so they have to get their own revenues. Nevertheless, some of the protests have been successful and police have stopped their actions at those spots.

Interestingly, the former Automated Enforcement System (AES) which became AWAS (the Automated Awareness Safety System) – the system of automated cameras to take pictures of vehicles exceeding speed limits and not stopping at red lights – works in a similar way as ‘flashing’. However, it is the authorities who are alerting motorists of the presence of a camera ahead as there are large yellow vertical boards a few kilometres before the camera. This effectively makes drivers stick to speed limits, although there are still many who either don’t notice the boards or don’t care.

Speed limits are important for road safety because the majority of road-users are not necessarily skilled enough to handle high speeds. Those who can are usually in two categories – the reckless who get themselves killed because they take risks, and the proficient drivers who know when it is necessary to reduce their speed and to drive within their limits (even they may be higher than others).