WHEN a bowl, teapot, or vase falls and shatters into a thousand pieces, we toss it away in anger and regret. When we go around the world, the procedure or art of restoring shattered ceramics differs widely.

While the focus in the West is on making repairs invisible and restoring an object to its original condition as much as possible, yet, breakages in Japan are mended with gold pigment and lacquer, which leave a break clearly visible and transform the appearance of the piece.

What is Kintsugi ?

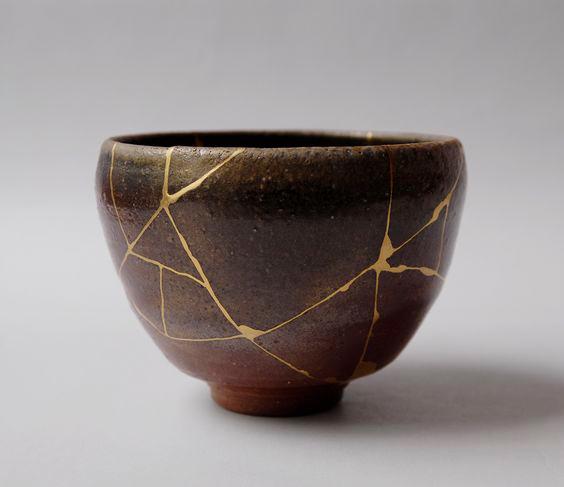

It is a traditional Japanese artwork that uses a precious metal – liquid gold, liquid silver, or lacquer dusted with powdered gold – to put together the parts of a shattered clay item while also enhancing the cracks. The process entails connecting fragments and giving them a new, more refined appearance. Because of the randomness with which ceramics shatters and the odd patterns generated, each restored piece is unique.

A broken tea bowl

Kintsugi began in the late 15th century, when Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a damaged Chinese tea bowl back to China for repairs. When it was returned, fixed with unsightly metal staples, it may have inspired Japanese artisans to seek a more aesthetically pleasing method of repair. Collectors became so enamoured with the new art form that some were accused of purposefully shattering priceless pottery in order to fix it with the gold seams of kintsugi.

Kintsugi became linked with ceramic jars used for chanoyu (Japanese tea ceremony). Also linked to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which embraces the flawed or imperfect. Japanese aesthetics appreciates worn marks caused by object use. This can be interpreted as a reason for maintaining an object even after it has broken, as well as a justification for kintsugi itself, stressing the cracks and repairs as just an event in an object’s existence rather than allowing its service to cease at the time of its damage or fracture.

Kintsugi is related to the Japanese philosophy of “no mind” (mushin), which includes non-attachment, acceptance of change, and fate as parts of human existence.

Paul Scott, a British artist, creates art using the kintsugi technique as well. By disrupting the classic shape of blue and white transferware, he calls attention to political and social themes while defining his pieces as collages. Scott, for example, created ornamental plates depicting the humanitarian catastrophe in Syria in the style of ancient pastoral sceneries and floral patterns in his Cumbrian Blue(s).

Bouke de Vries, a Dutch artist, studied ceramics restoration and learnt the traditional kintsugi procedure from a Japanese lacquer specialist. Now, he uses this technique to construct sculptures, such as his well-known War and Pieces, which was inspired by the sugar sculptures prevalent among European aristocracy in the 17th and 18th centuries. The artist utilises kintsugi to improve his sculptures and is captivated by its longevity. He uses clay in a variety of ways, from fixing Chinese pottery to producing ceramic birds and flowers.

According to Christy Bartlett, the acceptance of accidents and faults, which is rooted in Japanese philosophy, “carries overtones of fully existing within the moment, of non-attachment, of equanimity amid shifting situations.” Perhaps this is why the interest in kintsugi hasn’t faded even today.

Why is this art important to us as humans?

You probably don’t expect others to be perfect. You may appreciate it when individuals expose their vulnerabilities, show old wounds, or admit faults. It’s proof that we’re all fallible, that we heal and evolve, that we can withstand blows to our egos, reputations, or health and live to tell the tale. By acknowledging mistakes and exposing weaknesses, partnerships gain closeness and trust, as well as mutual understanding.

Even while we are often relieved when people are truthful, we are hesitant to expose ourselves. We value other people’s candour about their mistakes, but we find recognising our own failures far more difficult.

This occurs because we understand other people’s experiences abstractly while seeing our own extremely concretely. We are intimately and physically affected by what happens to us. What happens to others, on the other hand, operates more like an instructive narrative, because the pain of failure isn’t ours, and the distance provides us perspective. In theory, we can all agree that horrible things can happen. But when they happen to us, we feel terrible and condemn ourselves.

Vulnerability is boldness in you, but inadequacy in me: that’s simply incorrect. Imperfections, like the kintsugi artisans who long ago restored the shogun’s bowl with gold, are gifts to be worked with, not shames to be hidden.

Make the ordinary extraordinary

It’s ridiculous to be ashamed of our mistakes and failings in life because they happen to everyone, and no experience is wasted.

Everything you do – good, horrible, ugly – can serve as a life lesson, even if it’s something you’d never do again. In fact, mistakes might be the most valuable and successful learning experiences of all. And it can be shared truthfully with those who are in need and deserve to receive that information.

Things might go apart. That’s just life. But if you’re wise, you can use every piece of material to patch yourself up and keep going. That is the essence of tenacity, resilience, and perseverance. The name is “mottainai”. Some philosophers say that it is the true meaning of life.

When we expect everything and everyone, including ourselves, to be perfect, we not only discount much of what is beautiful, but we also create a cruel world in which resources are wasted, people’s positive qualities are overlooked in favour of their flaws, and our standards become impossible to meet, restrictive, and unhealthy.

Instead than leaving us forever searching for more, different, other, better, the kintsugi approach makes the most of what already is, highlighting the beauty of what we already have, imperfections and all.

In other words, your existing experiences and personality enough. You may occasionally chip and break, necessitating maintenance. That’s perfectly fine. However, the best and most abundant material on the earth is freely available to anybody, and we can all use what we already have – even our imperfections – to be even more beautiful.

After all, our flaws are what define us. And allow us to shine!