IRON is an essential mineral necessary in the production of haemoglobin in our red blood cells. It is also an important part of the neurologic development of infants and children.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide and remains a major public health issue, especially in developing countries. In Malaysia, the WHO reported in 2016 that the overall prevalence of anaemia among children aged 15 years and below was 24.6%, where the majority of cases were due to iron deficiency.

The most common cause of iron deficiency in children is inadequate intake of iron. As picky eating and an imbalanced diet are common problems, especially among young children, the result is inadequate iron intake to match the daily iron requirement of 7mg in infants and toddlers.

Another important cause of iron deficiency is maternal iron deficiency during pregnancy. Thankfully, it is less commonly seen now due to better awareness and the widespread practice of providing iron supplements to pregnant mothers.

A premature baby has higher iron requirements and lesser iron stores and thus is at risk for iron deficiency. Other than that, exclusive breastfeeding beyond six months of age provides inadequate iron for babies. Also, excessive formula milk intake without adequate supplementary diet after six months old does not provide enough iron.

Iron deficiency is also commonly seen in families who are vegan due to the lack of readily absorbable heme iron found in meat. Children with chronic illnesses with blood loss or malabsorption are at risk of developing this nutritional deficiency as well.

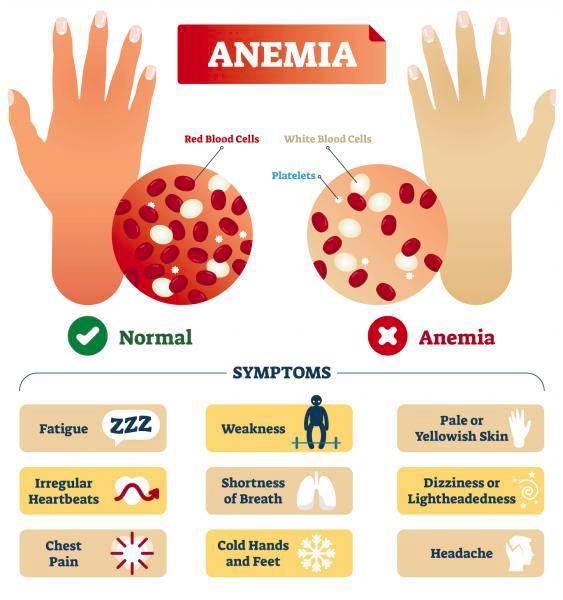

As the majority of iron in the body is used in the production of haemoglobin, the most important clinical manifestation of iron deficiency is anaemia. In the earlier stages or in mild anaemia, there are no apparent identifiable symptoms and thus is easily missed. A significant number of cases of anaemia are picked up by chance during blood taking for other reasons such as visits to the hospital for infections.

If left untreated, some of the progressive symptoms include a pale appearance and reduced stamina for physical activities. In the long term, iron deficiency affects the cognitive development of children which reduces their learning, memory, and mood. This prevents the child from achieving their maximum learning potential. Some studies have shown that these effects persisted for up to 10 years even after treatment, placing an added emphasis on the need to prevent iron deficiency.

When iron deficiency is suspected, some of the investigations that may be performed include the full blood count, peripheral blood smear, and iron studies. The normal range of haemoglobin varies depending on age and gender.

The haemoglobin value will be lower than expected for age, and the red blood cell will appear to be pale and smaller than normal. Iron and ferritin levels will be low.

Some examples of iron-rich foods include red meat, chicken, fish, fruits and green leafy vegetables. The two forms of iron available are heme iron and non-heme iron. Heme iron is more readily absorbable and is found in meat, fish, and poultry, where the body takes in up to 30% of the consumed heme iron. Non-heme iron is found in plant-based food such as fruits, vegetables, and nuts, and only 5 to 10% of consumed non-heme iron is absorbed by the body.

Certain foods such as bread, wheat, and baby cereal are artificially enriched with iron to help increase iron intake. Information on iron-rich food is easily available online.

To help boost the absorption of iron, one can also include a source of vitamin C in the diet.

Some feeding tips to help manage picky eating include:

-> Set a regular mealtime every day, as children feel most comfortable with scheduled timing

-> Serve small meals and snacks at consistent times which allows the child to be sufficiently hungry before the next meal

-> Eat together as a family to set a good example

-> Try to avoid distractions such as screens during mealtime

-> Encourage independent feeding and make mealtimes a fun occasion

-> Systematically introduce new foods by providing a small amount of new food with their usual favourites.

-> Refrain from bribing, forcing, or tricking them into eating. If they refuse, try again after a few days or a week, as it may take time for them to get accept new foods

-> Limit mealtime duration to 30 minutes, remove food after this duration, and offer food again at the next planned mealtime

Dr Yeap is a paediatrician attached to KPJ Sentosa KL. Through his articles, he aims to help increase public awareness of the common issues associated with children’s health.