EUROCENTRISM often claims itself as the normative and dominant framework of ‘modernity’, while sidelining ‘other’ fashion and aesthetic forms as quaintly traditional. How can we break free from the effects of this false dichotomy?

This served as the starting point for Swedish-Malaysian fashion designer Azura Lovisa to dismantle the value judgments that cause traditional styles to be at the other end of the pole from modernity. For cultural appropriation and colonial injustice cannot be rectified without reckoning the systemic issues built into the fashion industry – its distinction from mythology and folklore, ritual and craft as cultural identities in society.

“We can begin to decolonise aesthetics by resisting the traditional versus modern binary, and insist on exploring non-Western culture with the same depth of attention as Western aesthetic history,” said Azura.

The Central Saint Martins alumni explored Orientalism and post-colonial identities in her graduate collection, drawing inspiration from her family photo archive that has images of Malaysia from the 50s and 60s. She saw the convergence of traditional Malaysian folk dress with influences of British tailoring and style that gave rise to forms of hybrid fashion.

“Similar surprising evolutions and adaptations have echoed across other former colonies around the world. I felt compelled to create a brand with hybridity at its core, looking to Southeast Asian aesthetic heritage as the starting point,” she said.

“I wanted to interrogate why people relegate folk dressing to relics of a ‘tribalistic’ past. In pursuing alignment with the Western model of progress, traditional garments through which people once proudly projected cultural heritage, have largely been replaced by T-shirts and jeans as the contemporary uniform from America to Asia.”

It was never Azura’s intention to modernise the traditional. Her approach is to weave the traditional into our modernity, by supporting traditional crafts and expressions. This helps to provide the ingenious makers with income to maintain the artforms and keep them alive for younger generations.

“The traditional is alive, it is evolving and shifting all on its own. I don’t think we should consider it in terms of whether modernising the traditional is appropriate, evolution will happen regardless of how we feel about it,” she added.

Azura admitted that no matter how deep she delves into her Malaysian heritage, it will always be through a hybridity of gaze and from an outsisder’s perspective looking in. But it is precisely the gaze and gestures that reflect her practice, simultaneously the lens through which she sees, and the subject she is investigating.

Considering to what extent does Malaysian heritage influence her work as a designer and artist?

“I don’t speak Bahasa Melayu and have never lived in Malaysia. I am therefore a perpetual student with my Malaysian heritage. And like other mixed-race people, we must discover for ourselves what parts of our heritage carry weight for us. We must also often write new stories for ourselves.”

“I decided that rather than to let this deny my claim to my roots, I would make my hybridity the very core of my practice,” she replied.

Although her initial work bore more obvious references to her heritage, it has now become more implicit.

“Fashion is an appropriate medium for tracing cultural flows and tensions because it inherently contains histories and memories. It is also adapted to the contemporary reality, reflecting currents of change and tastes of the moment.”

Clothing mythology symbolises the possibilities clothes represent

“Clothing Mythology” – a concept coined by Azura to clothe mythology itself as well as mythical figures through the lore of clothing – seems to be a helpful play on fantasy through which to critique the present. And thus, can clothing mythology be described as speculative clothing?

Speculative encourages post-critical and experimental interpretation when analysing representations to supplement it with new alternative stances beyond standard practice. It is necessary that we engage the space between the imagined and the real to criticise our current reality, by dressing it and giving form to the reality we hope for.

“I love the idea of describing my work as speculative clothing, as it relates to speculative fiction. I enjoy these parallels to literature but I hadn’t thought to frame it like that before.

“Speculative fiction possibly has a broader scope, it opens up space beyond mythology when responding to uncertain realities and future possibilities. But whatever terminology you use, I think it alludes to the same idea, which is to recognise it is through storytelling that humanity has understood and assigned meaning to the world,” she said.

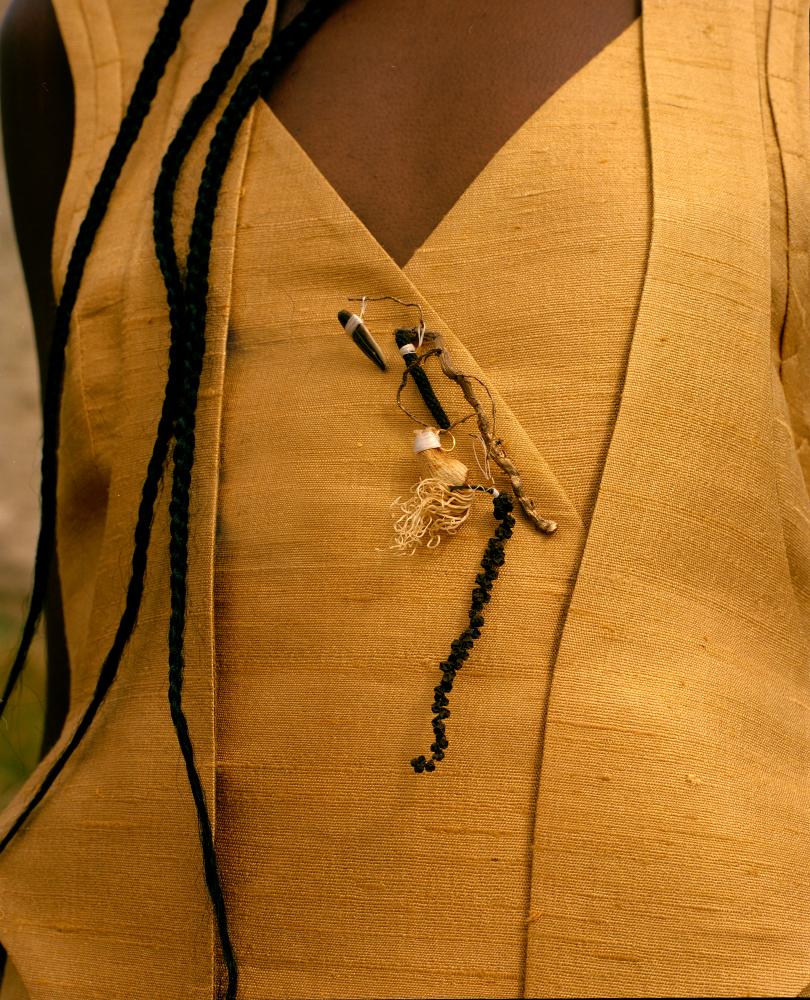

“Clothing mythology symbolises the possibilities clothes represent. They can transform us and physically, materially express what we hold within, or who we imagine ourselves to be. They can stir feelings and evoke memories. And, in the cloth itself, entire tales can be woven. They can show traces of the weaver’s heritage and histories in the designs of its patterns. Clothing holds stories within it as well as becoming part of how we tell our own stories.”

Azura’s designs feature handwoven heritage textiles sourced from cottage industries and weaver-owned businesses to empower rural communities and sustain legacies of traditional craft.

As a result, her gender-fluid clothes appear ethereal and regal, for some might be difficult to find an occasion to wear. Yet, she believes that there is power in casting those who wear her clothing as otherworldly beings in mythical narratives.

“Mythology is dynamic, we engage and perpetuate mythologies every day, giving our lives purpose, so why not fully immerse ourselves in our vision?” she shared.

“Even if somebody can’t afford my clothes, I hope they understand what I’m trying to communicate, and I hope that empowers them.”