CONTEMPORARY artist Kayleigh Goh’s paintings are contemplative spaces for cathartic release and therapy.

As Goh describes it, the poignant endeavour of creating art is marked by the emotion of a “self-reflective, introspective and meditative state. It’s always fulfilling when an abstract emotion is resolved and understood through the process of making.”

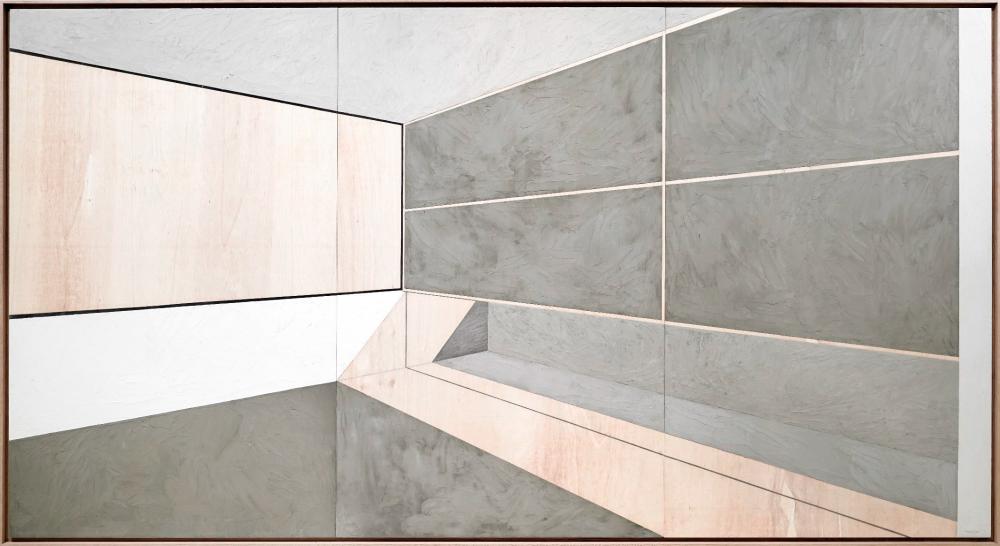

In her non-linear and nonrepresentational work which resembles colour field paintings, unbroken surfaces of the canvas are flooded by planes and panels, using stone-cold industrial materials as her vehicle of expression, rather than colours. And with it, the crude and ordinary materials are freed from objective context and become the subject themselves.

Goh employs the all-too-familiar features of textured cement and exposed wood to interpret the concrete jungle as an unoccupied space, that invoke virtues of its surrounding environment. It’s a composite collision between Brutalist quality and Zen sensibility to achieve structural clarity and spatial simplicity.

“I’m not so interested in the bold and dramatic sense in Brutalism, but I’m interested in the raw and honest quality of it,” she adds.

“Like Zen, it’s in the simplicity and directness of the materials. I understand that curved, rounded and nest-like spaces feel more embracing and soothing, but I’m interested in how strong perpendicular lines can be seen as support structures; that with their strength, reassure us.”

Hard and angular edges that suggest the cold and brutal nature of modernism have served as paradoxical spaces of healing and comfort, yet Goh uses these empty spaces within concrete walls to conjure a pensive state of mind.

She shares: “Art helps us re-balance in difficult times; to remember, share and record a communal experience when words are difficult. It can empower and inspire; in turn, changing one’s perspective and encouraging and motivating.

Share with us your earliest influences in art.

“My grandmother and mother were seamstresses, we have a tailoring studio space in our house and they hired some assistant seamstresses to help around too; it’s a family clothing business.

“As I watched my grandmother cut and sew, I liked the feeling of the space, it’s busy but it felt exciting to see how humble materials are turned into works of art.

“I didn’t pursue painting thinking I’d become an artist myself. I didn’t have formal training when I was younger, and I felt that I wasn’t talented enough. I decided to do fine art during my tertiary studies, simply because of the desire to know more about painting, the materials, the history behind it.

“It got more interesting as I learnt more about it, and everything developed from there. It was a scary choice, but I am really grateful to have made that choice.”

You may not have dabbled with the Brutalism movement when you started, but its qualities have become apparent in your work. How do you translate the post-war architectural movement in postmodern times?

“It’s true, I learnt about Brutalism after I’d started to paint using cement and wood, rather than before. In Brutalism, a respect for the materials is emphasised by showing honesty, without any ornamentation of the materials and the structures of the buildings.

“I was inspired by Japanese architect Tadao Ando – he uses concrete walls – the grey, neutral empty space brings a focus to the surrounding natural elements of light and air, and spatial experience.

“It’s also the idea about how without superfluous ornamentation and distraction, we can gain clarity.

“I’m interested in exploring the materiality of paint and other materials in my work. How the raw quality of paint, wood, glass and foraged pigments can be shown through the work rather than by using paint to cover up, to represent and illustrate.”

Ando’s work has been labelled as ‘Critical Regionalism’ extending beyond the sense of vernacular architectural movement. Could you share with us how you’re able to resonate with his work?

“About Critical Regionalism, in British architect Kenneth Frampton’s essay, he cited French philosopher Paul Ricœur, asking “how to become modern and to return to sources; how to revive an old, dormant civilisation and take part in universal civilisation”.

“It’s about finding a way to use contemporary universal language, yet at the same time holding firmly onto one’s own social, cultural identity in their practice.

“Tadao Ando’s practice reflected a contemporary way of exploring Japanese aesthetics. He mentioned that he is influenced by Shintoism and Buddhism. Perhaps, the structure he created, the material of concrete is the “modern” and what is reflected – his way of thinking, using the materials, the surrounding elements, etc. – are the “sources”, mentioned in Ricoeur’s writing.

“I interpreted his architecture as an empty vessel that can hold and reflect the surrounding environments. It is created to work as a contrast to the natural elements, rather than being plainly about the architect building itself; it goes beyond the building. He uses contemporary materials and methodologies, yet at the same time, considers and uses the methodologies reflected in his social, cultural and historical background.

“I find the resonating point to be perhaps in the crossing of the religious influences. Japanese architectural and aesthetic theories have been rooted in Shintoism and Buddhism, and many Chinese ink paintings ideas are too grounded in Taoism and Buddhism teachings.

“As I explored my Malaysian Chinese identity earlier in my practice through Chinese ink paintings, Japanese Zen paintings led me to Japanese architecture and aesthetics, and thereafter to Ando’s practice.”

Some artists open their work to interpretation, while others control the narrative. Where do you stand?

“For now, I am in the middle. I need to reflect myself in each of my works, and as I understand how and why for myself, I do explain and articulate it when I am asked about my intention with the works.

“But I see myself as creating a space for an individual’s contemplation and reflection, from there the narrative gets personal. The paintings are spaces for that narrative, the titles are like trigger points to engage with personal narratives. [I’d rather be a] listener than a speaker.”

Do your living spaces reflect the characteristics of your art as well?

“Definitely. Cultivating an art practice has changed me as a person over the years, and as my practice is closely related to spatial experience, it has also changed how I arrange my everyday space.”