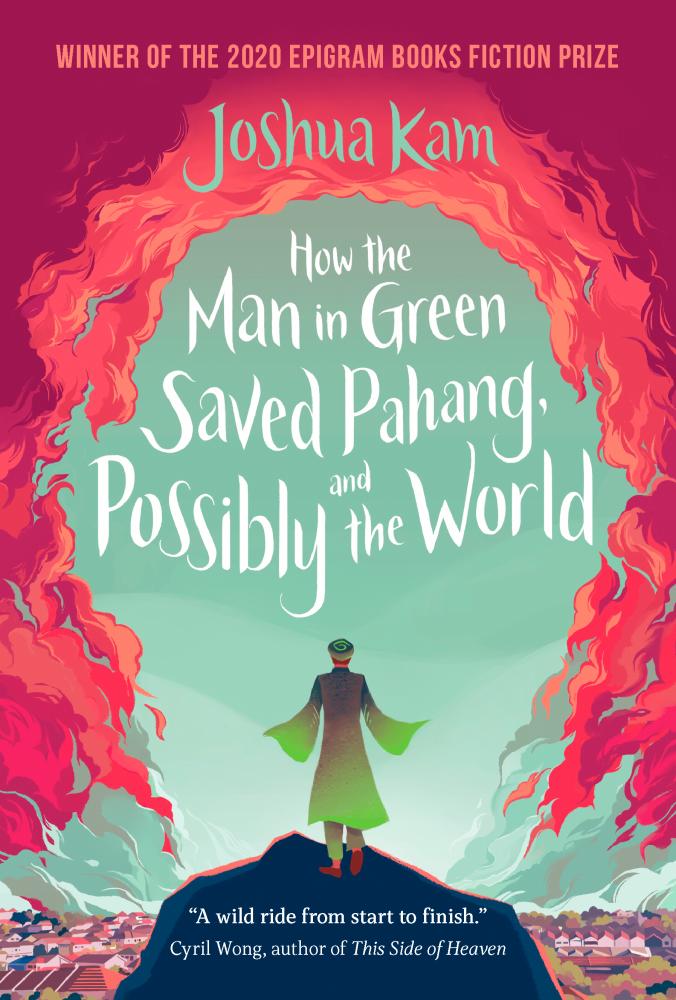

It has been a long journey for author Joshua Kam, whose manuscript How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World won the 2020 Epigram Books Fiction Prize earlier this year.

He said: “I remember growing up and longing to tell stories that resonated with my own nostalgias; connected to my own tanah air (homeland). I think that’s why I decided to study Malay, Chinese, and Javanese manuscripts for a living.”

By winning the prize, the 24-year-old also secured a publishing contract with Epigram Books to have his manuscript turned into a book.

As a history graduate of Hope College, Michigan, Kam’s fascination and obsession with mythology is rife within his first novel.

But the writer admits he is far more interested in Asian mythology compared to those from the West, which serves as the core of How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World.

How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World. – PICTURES COURTESY OF EPIGRAM BOOKS

Childhood and mythology

Though he refers to himself as a native of Kuala Lumpur, Kam pointed out that his family roots stretch as far as Penang, Seremban and Kuantan.

As a child who grew up in Kuala Lumpur, he recalled how his parents and grandparents often sparked the fires of his imagination during long car rides with mythical stories.

“(These were) stories from the towns that dotted the countryside, both real and imagined, of rabbits living on moons and ships full of saga seeds sent by Malay kings to their rivals and good widows and huge gobies in Pahang creeks,” he said.

“I think it was this particular interweaving of land and narrative that drew me in, as I grew older and jumped into the wide world of western fiction.

“The myths and stories from western canon, however gorgeous, had no room for me. I didn’t grow up in some English cottage. The heroes of those stories don’t look like me, but the villains did.

“These were disembodied nostalgias; stories about westerners going off on adventures in spaces, lands, and times that didn’t resemble my own.”

Kam’s debut books tells an intersectional story of two leads: Gabriel, a church chorister who comes across the enigmatic character in the book’s title, and Lydia, a young theologian who has come to Kuantan to settle her late grandaunt’s will.

“It’s ultimately a book that tries (tries!) to examine the state of our country amid the backdrop of our cherished myths and ideas,” he explained.

“Part metaphysical thriller, part magic realist roadtrip, part love letter to the hidden histories of Malaysians the history books don’t mention.”

Inspired by mythology

Like most of his projects, Kam’s book began with a single image.

“It was this image of Nabi Khidir, the green-clad prophet from Hikayat Hang Tuah, brushing the dust off his robes in the middle of Masjid Jamek LRT station,” Kam said.

“There was something riveting about the image of Sufi prophets from Melayu hikayat popping up in 2018 KL. Inspecting the steel bars, the cement, the cendol seller’s ice-grinder, the neo-Mughal domes of the mosque.

“What would they think of us and our country? What acts of magic and healing would they do here?”

He further pointed out that penning the story was no easy feat, due to the cutting across of several different perspectives and lived experiences, which Kam thinks was one of the greatest challenges in writing the book.

“I don’t claim any authority of ‘The Malaysian Experience’, whatever that means. I don’t know what it was like to be a Pahang Chinese aunty during the Emergency, any more than I can speak on other intersections I don’t occupy.

“The hope, I think, was to tread lightly through stories that I’m borrowing, always citing my sources and doing justice to the characters I wanted to portray.

“In a sense, my book is far less a call to traditionalism than a call to make our traditional myths living and active, not frozen and dead. I think there’s certainly a trend to cultivate nostalgia for so-called golden ages. Be that Melaka before the Portuguese, or the British colonial days when the “post office still ran on time,” etc.

“There’s a desire to freeze the past into a stiff image, a purist’s version of a time when things were right. But the myths outlive the people who made them.

“They keep changing, keep speaking to new people, keep encouraging us to examine parts of Malaysian history we don’t often encounter.”