AZZAH SULTAN’S debut solo exhibition Anak Dara in New York is an ode to the diaspora of leaving home, and her journey to reclaim a personal and generational narrative through the materiality of cultural fabrics, while exploring the idea of femininity in a matriarchal setting.

The Malay term ‘anak dara’ is colloquially used to describe a young, unmarried female. “It’s a term of endearment my mother often uses,” the 24-year-old artist explained.

She says: “Creating and exhibiting a work about Malaysia while being abroad felt like a form of therapy. I get homesick a lot, and being so far away from my parents makes me emotional. Thus, creating this work or space that felt like home was also a way for me to be more connected to my identity and cultural heritage.”

Despite spending her formative years growing up in Saudi Arabia, Finland and Bahrain, and now residing in America, Azzah – who is of Malay, Indian and Pakistani descent – says: “Malaysia will always be my home as it is where my family is.

“My relationship with faith and the Malaysian culture are inseparable. For me, ‘home’ is being around with your loved ones; that being my family and even the friends I’ve gotten close to in America.”

When did you first start to think outside of the canvas as an artist?

“When I started focusing on issues very personal to me, I came to realise the importance of time-based media. I began with a strong focus on painting, but eventually, when I shifted my focus to issues like race and identity, I felt like the medium needed to be more complex in order to reflect the importance of the content in a nuanced way.

“The turning point for me was when I started creating a series of video pieces and performance art that illustrated what Islamophobia looked like in America.

“At times I get inspiration from the materials I have, the core drive for my art will always be to express the frustration that I experience.

When you’re making art about faith, heritage and culture rooted in displacement, do you think there will ever be a time where you get out of that frustrating outlook?

“We’re constantly living within a society that is deeply rooted in racism, sexism and xenophobia. There are moments where I do make art for fun but because of who I am as an artist, that will still get twisted into something political, there is no escaping it.

“For a long time, I never wanted to make art like this because it’d seem like a cliche. But I’ve been ingrained to think that way because of criticism I’ve faced which placed me within a box. The difference now is that I’m making art that is coming from my narrative, I’m not giving all my secrets away or diluting my work to make others comfortable.”

Is it possible to create works that highlight Muslim women’s narratives in a way that is not predicated solely on stereotypes and stigmas?

“Of course! There’s so much more to Muslim women than the stereotypes and stigmas we face. At first, I did create work about women that share the same identity and faith with me, but after a while I found it to be quite redundant; which is why I’m making the switch towards my relationship with home and my culture.”

Can you give an example?

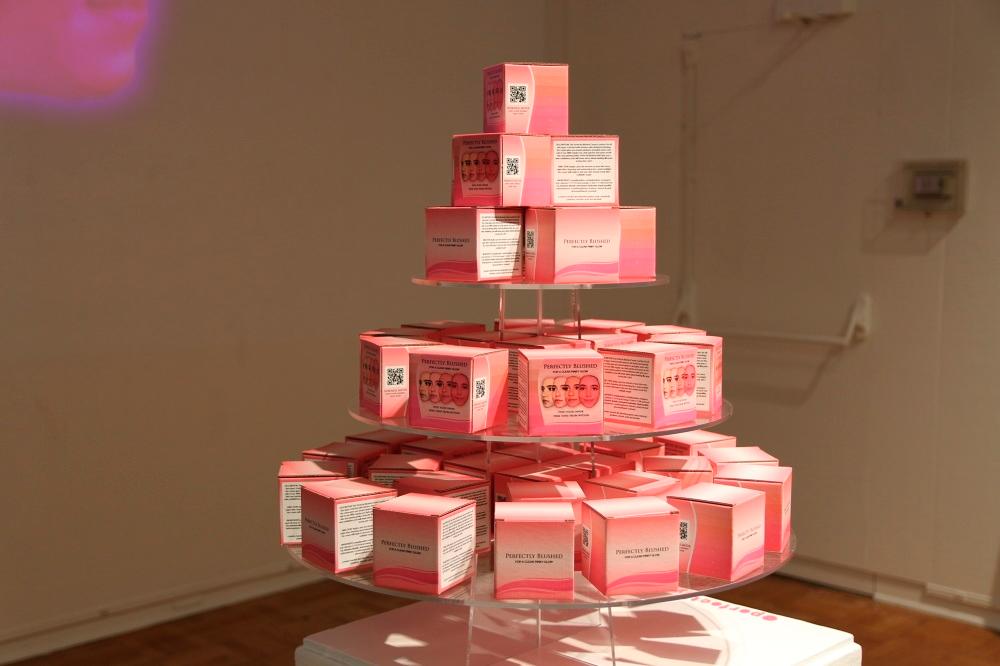

“Before Anak Dara, I had a video installation called Perfectly Blushed (2019), highlighting the beauty standards placed on women of colour through the use of skin bleaching products, as [their marketing] promises a successful future.

“The idea with Perfectly Blushed was to create a product that reveals how harmful these skin bleaching products are, and the detrimental effects these ingredients have on our physical appearance and mental health.

“I intended to have the audience question what it means to change your skin tone – to assimilate yourself in imposed beauty trends that stem from white supremacy and a long history of colonialism.

“I wanted to make this piece, not as an attack on women who use these products but more on the marketing and the industry behind them, so that it doesn’t just end with a problem but at least instigates questions on how to change it.”

Your work Home Sweet Home (2016), stood out particularly to me for its controversial and provocative narrative to address cultural power structure while countering Islamophobia. Do you see yourself as an activist?

“It’s a special piece for me, created around this time four years ago, where I felt powerless being a Muslim woman and an immigrant in America when the presidential election was going on.

“There are so many great activists out there, and I feel like I still have a long way to go to even achieve that title, but there is an urgency of activism within my art. I use my art as a form of creating awareness, hoping it’d start a dialogue.”

It’s incredible to see how activist art is able to criticise and confront the social order, revealing truths about society’s conflicting opinions that are otherwise uncomfortable.

“Exactly! A piece that highlighted the problem with the male gaze was my Oriental Woman (2016) performance art. In this piece, I collected images of Orientalist-styled paintings of Eastern women by European artists between the 18th-19th centuries, which clearly embody the ideas of fantasy, myth and exoticism.

“Orientalism as art creates a female counterpart to the masculinity of Europe – that the women serve as a sexual object, and a culture that represses women and creates a fantasy of feminine mysticism.

“These collected images were presented in a video and then projected onto me, while I performed traditional Malaysian dances. It revealed a conflicted position I am in, by demonstrating my culture and trying to defeat the exotic views of Muslim women.

“A lot of men argued with me when they saw this performance art because it shed light on their own internalised misogyny. I feel like it’s important for art to illustrate people’s biases so we can be more self-aware and learn how to be better.”