FRESNO: With planting season well under way in California, the leading US food-producing state, fear is taking root among thousands of migrants who labor to feed a country that now seems ready to deport them.

“We have to stay hidden,“ Lourdes Cardenas, a 62-year-old Mexican living in the city of Fresno, told AFP.

“You are unsure if you will encounter the immigration authorities. We can’t be free anywhere, not in schools, not in churches, not in supermarkets,“ said Cardenas, who has lived in the United States for 22 years.

President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric has left people like her “depressed, sad, anxious” and fearful of being deported, she said.

Cardenas is one of more than two million people working on farms in the United States.

Most were born outside the country, speak Spanish and, on average, arrived more than 15 years ago.

Still, 42 percent of them lack the documents that would allow them to work legally, according to the government’s own figures.

In January, surprise raids by immigration officials in Bakersfield, an agricultural city about 250 miles (400 kilometers) from the Mexican border, sent chills through workers in California’s breadbasket Central Valley.

They were a stark reminder that the country some of them have called home for decades elected a man who wants them gone.

“We were not afraid of the pandemic,“ said Cardenas, who did not stop working during the worst months of Covid-19. “But right now this is getting bad for us.”

Lower wages

While they might be staying away from church, or altering their shopping habits, the one thing these migrant workers cannot do is stay away from work.

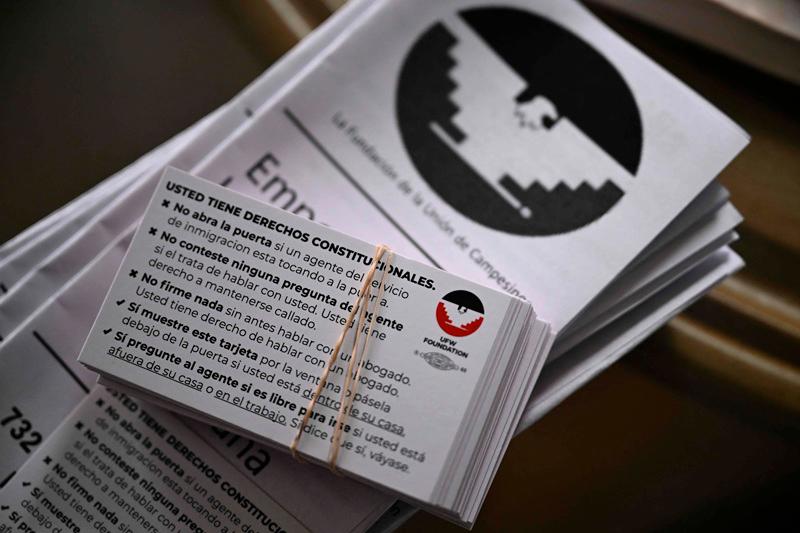

That is why for the United Farm Workers, the largest farm workers’ union in the United States, the threatened mass deportations will not translate into more jobs for Americans.

Instead, they say, it will further drive down the cost of those migrant workers, making employers less likely to pay them the much higher salaries that American workers demand.

“You have thousands of people who are so afraid of being deported that they’re willing to work for way less,“ union spokesman Antonio de Loera told AFP.

“They’re not going to report wage theft. So if anything, it’s undercutting the value of American workers.

“This status quo serves the interest of many employers in the agricultural industry. For them, this is the sweet spot,“ de Loera said.

“They have their workers but their workers are so afraid that they won’t organize, they won’t ask for higher wages, they won’t even report violations of labor law or unsafe working conditions.”

There is, he said, a fairly simple solution: grant the workers legal status.

“Once they are US citizens, then we’re all competing on a fair, level playing field. We all have the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.”

Trend to automation

The overall uncertainty offers an opportunity for companies that manufacture increasingly automated machines.

“The agricultural community depends a lot upon migrant labor and if they’re no longer available or able to get to work, we need to help come up with solutions,“ said Loren Vandergiessen, a product specialist at farm implement maker Oxbo.

The company was one of a number present at the World Ag Expo, the largest agricultural exhibition in the United States, held last month in Tulare, north of Bakersfield.

Its line-up included a berry harvester the company estimates reduces labor requirements by up to 70 percent.

Cory Venable, Oxbo’s director of sales and advertising, said automation can help a farmer’s bottom line.

“It’s becoming harder to find people to be able to do this work,“ and labor costs are challenging, he said.

“So by having this type of technology, we can decrease that sum.”

Gary Thompson, director of operations for Global Unmanned Spray System, was showcasing a device that can allow one person to operate a fleet capable of doing the work that would require up to a dozen tractors.

“Over the years, the labor challenges just continually get more and more difficult: the shortage of labor, the cost, the regulations involved,“ he said.

“The farming industry is really looking at autonomy, not as just like, oh, that’s something in the future, but it’s something that’s happening now.”

But for those already laboring in the fields, such machines can never replace the human touch required for picking grapes, peaches and plums.

“A machine will destroy them,“ said Cardenas, “and we cannot.”

“We farmers are indispensable.”