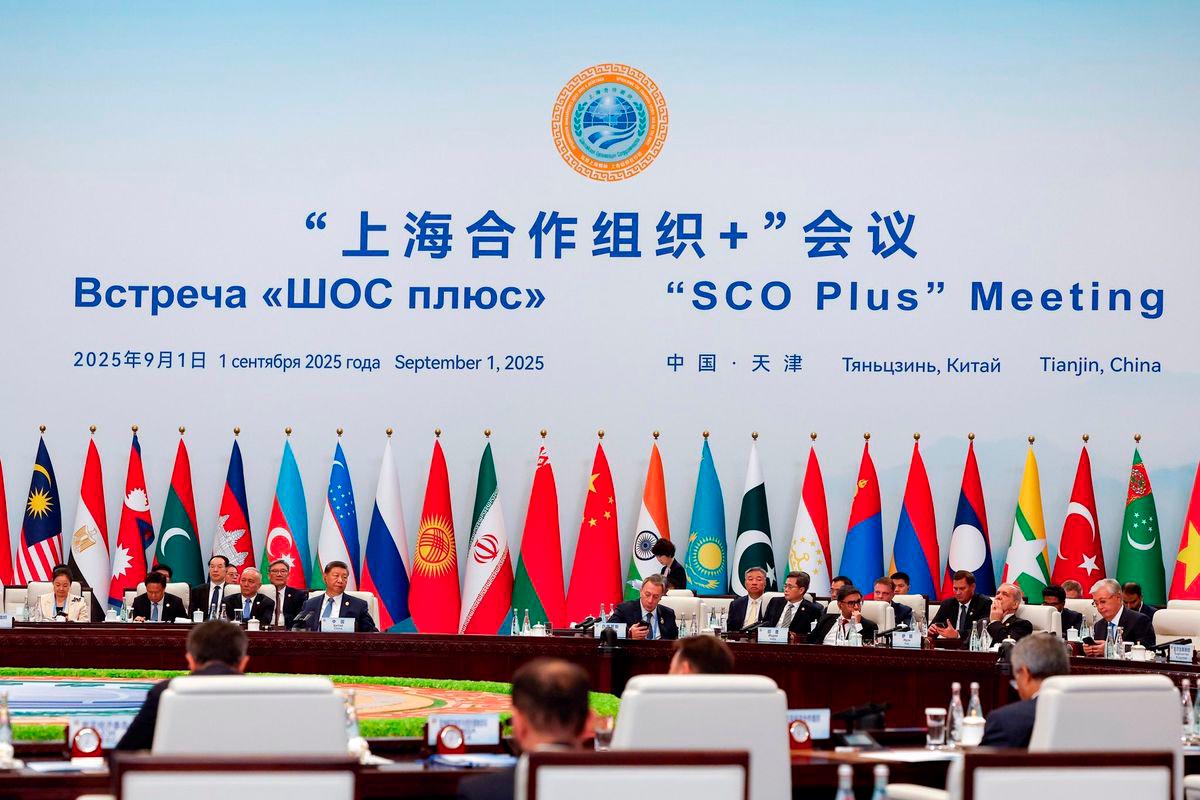

AS world leaders, including Malaysia’s Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, converged in Tientsin recently for what non-Western media are describing as an unprecedented, pivotal and potentially transformative meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), their counterparts in the Western world have responded with slanted and partisan reporting.

This arises in part from their long-held mantra that the SCO is a club of autocratic countries whose development and even legitimacy need to be opposed and pushed back against.

Some mainstream United States and United Kingdom media organisations have gone to the extent of refusing to send reporters to cover the event or have consigned brief mentions to the inner and least conspicuous pages of their papers and social media posts.

A few of the most respected, on the other hand, have jumped on the event to provide their readers with alarming analysis of the latest “existential threat” and “axis of upheaval” to the international, that is, Western governance system.

It is not a mystery why the Western world leaders and their geopolitical think-tanks are paying special attention to this meeting. Together with BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and expanded members), the SCO has rapidly emerged as the most formidable challenge to the prevailing global order dominated by the US and its predominantly Western allies through institutions like the G7 (Group of Seven), Nato (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (WB).

Emerging counterweight of SCO

The following features of the SCO make it an emerging superbloc in international relations and geopolitical dynamics.

The grouping, though having an innocuous sounding name, possesses significant geopolitical, economic and strategic dimensions and clout.

Expansive membership and demographic weight

The SCO is the world’s largest regional organisation by geography and population, covering 80% of the Eurasian landmass and 40% of the global population. It includes 10 members (comprising of China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Belarus), two observers (Afghanistan and Mongolia) and 14 dialogue partners (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Bahrain, Cambodia, Egypt, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates), representing a diverse and influential coalition. Cognisant of SCO’s importance in the global arena of politics and economics, among Asean member countries sending heads of state and governments to the meeting are Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia,

Thailand and Vietnam; with the Indonesia president cancelling his trip due to urgent developments on the home front.

Economic potential and resource control

The SCO accounts for 20% of global GDP (as of 2021) and controls 20% of the world’s oil reserves and 44% of natural gas reserves, especially after Iran’s accession in 2023. Trade among SCO members is substantial. For example, China’s trade with other SCO members reached US$512.4 billion (RM2.17 trillion) in 2024. Initiatives like the SCO Energy Club, established in 2013, and the SCO Interbank Consortium aim to enhance energy cooperation and investment financing among members.

Security cooperation and counterterrorism

The SCO has made significant strides in regional security through its Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS). RATS has reported thwarting numerous planned terrorist attacks and dismantled terrorist training camps. It focuses on combatting the “three evils” – terrorism, separatism and extremism – and drug trafficking, accounting for 14% of confiscated drugs worldwide (2012–2017).

Institutionalisation and multilateral frameworks

The SCO is structured around consensus-based decision-making. Apart from its geopolitical focus, it promotes cooperation in areas like transport, culture, education and digital economy.

Challenges and potential

The organisation emphasises the “Shanghai spirit” – mutual trust, mutual benefit and non-alignment – which fosters a unique model of cooperation distinct from Western-dominated forums.

What has prevented SCO from being more effective includes the following:

Limited economic integration record.

Technical and geopolitical barriers to financial reform initiatives.

Internal divisions arising from conflicting interests between members, for example, the India-China border dispute that has hindered cohesive action, including on unrelated issues.

Institutional weakness arising from the absence of a unified treaty-based structure; and with its consensus model often limiting decisive action.

These internal divisions, differences and rivalries arising out of often competing national interests will continue. However, analysts previously unconvinced that SCO can become a formidable counterweight to Western dominance and the creation of a multipolar world order are beginning to revise their assessment.

Dragon and elephant convergence

Two developments have triggered this reassessment. The first is the rapprochement of India and China, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi attending the meeting and making his first visit to China in seven years.

The improvement in relations between the two leading countries of the world is having ripple effects across a wide range of international issues and fronts.

Already among them is the positive impact on SCO and its potential to offer a platform for non-Western voices, emphasising state sovereignty and non-interference. We can expect to see SCO – led by China, Russia, India, Iran and Turkey – to focus on security and regional stability and be more forthright in opposing Nato’s expansion and other Western-led geopolitical initiatives in the future.

The second comes from US President Donald Trump’s Maga (make America great again) policies, especially in the trade and economic field. Together with BRICS, SCO has opposed unilateral trade measures and positioned itself as a defender of multilateral trade.

The global tariff war that Trump has embarked on is just beginning. However, it has already severely undermined the global trade and economic order.

It is also accelerating institutional fragmentation and weakened the dominance of global governance by the US and its allies.

As G7, Nato and other Western supportive institutions struggle with internal divisions, SCO and BRICS are emerging as stable multilateral alternatives.

SCO and BRICS are not immediately replacing the G7-led order. But there is no doubt that they are accelerating its erosion by promoting multipolarity and offering alternatives to Western economic and geopolitical dominance.

Their ability to attract middle powers, resource-rich economies and Global South nations underscores the structural shift that has taken place in global governance as the world moves towards a more fragmented and complex order.

Lim Teck Ghee’s Another Take is aimed at demystifying social orthodoxy.

Comments: letters@thesundaily.com