THE Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail (KL-SG HSR) is more than a strategic initiative to cut Kuala Lumpur-Singapore travel time to an estimated 90 minutes.

It is a significant move to boost regional connectivity and economic growth, making Malaysia a vital part of the larger Pan-Asian Railway Network.

This role can become more crucial if the line later integrates with the Pan-Asian HSR, a project under China’s One Belt, One Road initiative.

Looking beyond its immediate benefits, the KL-SG HSR can play a significant role in addressing some of Malaysia’s long-standing issues, such as the lack of a highly skilled workforce, the need for high-value foreign direct investments (FDI) and a continuously depreciating currency.

However, we should note that without careful and meticulous execution, the KL-SG HSR can inadvertently lead to diametrically opposite outcomes. Harnessing HSR’s great potential for Malaysia involves more than just surmounting a daunting funding challenge due to constricted fiscal space.

Malaysia must undertake every measure to reverse the significant outflows of resources (financial and human capital) that have escalated and become entrenched over decades of inefficient governance.

As Malaysia’s profound brain drain and weakening ringgit evidently illustrate, in the globalised world, resources will always flow where they are needed and can be deployed most effectively.

Enhanced connectivity, without ironing out the destructive mechanisms within our country that initiated the resource outflows risks exacerbating these outflows, bypassing Malaysia as the key beneficiary and only perpetuating its role as not more than a resource appendage and market base for others.

High-value FDIs will not flock in simply “because we have HSR in place”. Savvy high-value investors consistently seek holistic foundational platforms where all crucial components are present and harmoniously integrated while low-value FDIs tend to exploit gaps in the system.

Demand for ringgit

The economic necessity of constructing the HSR reinstates the need to create organic demand for the ringgit as discussed by Emir Research in “Seizing opportunities to support sliding Ringgit”.

This is crucial to attract Singaporeans and our other neighbours, in the context of a long-term broader Pan-Asian integration, to visit Malaysia more and encourage them to spend on our products and services, thereby supporting the ringgit rather than the other way around.

This requires seizing opportunities within the tourism and entertainment industry, catering to international and domestic tourists. Such initiatives should include:

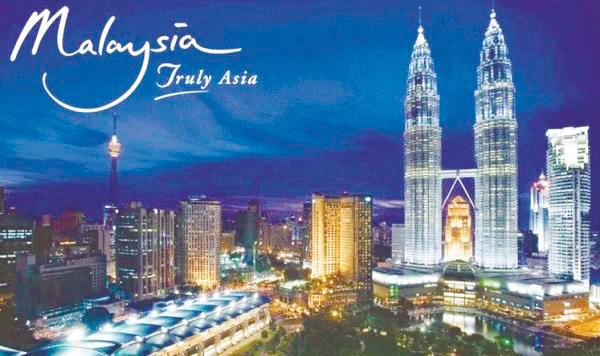

Revitalising the highly successful “Malaysia Truly Asia” campaign;

Developing new “adventure and sports tourism” attractions that have been on the rise globally and which in Malaysia can be plentiful due to its picturesque and diverse landscapes;

Taking “gastro-diplomacy” seriously;

Positioning Malaysia as a regional travel hub for a seamless Umrah experience by capitalising on its well-established network of Umrah facilitating agencies and close bilateral relationship with Saudi Arabia, which has resulted in one of the largest numbers of landing rights in Saudi Arabia; and

Rejuvenating “medical tourism” by addressing various persistent challenges within the healthcare industry, including the ongoing issue of brain drain. The policymakers must consider the 2024 Global Medical Trends Survey report, which forecasts Malaysia’s medical inflation to surge to 13.36% while placing Malaysia second only to the Philippines (13.94%) among its Asia Pacific peers with much better outlooks, such as Vietnam (11.33%), Singapore (10.67%) and Thailand (9.27%). Such figures cast doubt on Malaysia’s potential to thrive in medical tourism. Furthermore, if this trend is not checked, HSR could only exacerbate the ringgit outflows by facilitating Malaysians’ access to superior and more affordable medical care overseas.

Addressing brain drain effectively

The KL-SG HSR, if realised, may not immediately affect the number of highly skilled Malaysians relocating to Singapore, who seek not only superior work conditions and benefits but also a higher quality of life and public services, such as education and healthcare.

However, it preserves the potential to expand the current trend observed at the Malaysia-Singapore border, where many Malaysians live in Johor but commute daily to Singapore for work, extending this pattern to a larger geographic area.

This outcome is more probable without simultaneous comprehensive government efforts to tackle the primary push factors accelerating the Malaysian brain drain for decades.

Emir Research has identified these factors in its recent report, “Malaysian Brain Drain: Voices Echoing Through Research”, based on over 15 years of empirical data. They include inadequate salaries and perks; scarce job opportunities stemming from severe skill mismatches with local industries; limited promotion chances; restricted opportunities for professional and personal development; an unstimulating work environment; poor quality of life encompassing education, public services and quality of policymaking; safety concerns; economic instability; political volatility and institutional weaknesses.

Even without the KL-SG HSR, the allure of significantly higher salaries and the persistently weakening ringgit has consistently drawn many Malaysians to move to Johor, enabling them to make day trips to work in Singapore. These individuals, enjoying greater purchasing power, have been able to buy homes in Johor, markedly improving their economic status over time.

This trend is not limited to highly skilled workers, it also includes those with medium and low skills. Even individuals working in Singapore’s 3D sector (dirty, dangerous and difficult) earn considerably more than their counterparts in Malaysia for similar jobs.

A 2016 report noted that 600,000 Malaysians were employed in Singapore’s 3D sectors. Although these salaries were lower than those in Singapore’s high-skilled sectors, when converted to the ringgit, they surpassed some high-skilled salaries in Malaysia at that time, which was still the onset of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Furthermore, fast-forward to 2024, with the extensive use of advanced technology, Singapore’s 3D sector is no longer even characterised as “3D”.

Therefore, the HSR necessitates a complete reformatting of Malaysia’s 3D sectors as proposed by Emir Research in “Complete Reform of 3D Sectors Needed to Reduce Reliance on Foreign Workers”.

If the push factors driving the Malaysian brain drain remain unaddressed, the HSR, which will effectively increase the “geographic proximity” to Singapore, could remove barriers preventing more Malaysians from becoming day commuters to Singapore.

While they will continue to live and spend in Malaysia, their contributions to the foreign economy and value creation abroad will further widen the disparity between local demand and economic growth.

Human capital flight, encompassing highly-skilled, medium-skilled and low-skilled workers, may partially support the weakening local currency, improve the economic status of some family units and increase consumer spending.

However, it will also create critical voids in key local sectors, triggering a series of profound negative economic impacts, as Emir Research detailed in “Harvesting Genius: Unraveling the Complex Dance of Brain Drain”, eventually leading to more human capital flight.

Therefore, the HSR project must not be considered in isolation but alongside credible and decisive interventions to tackle key the brain drain push factors so that in the long-term, the HSR line can be strategically utilised to leverage a significant diaspora network in Singapore and stimulate economic growth and development.

Projects of national importance

It is imperative to ensure that the majority of Malaysian commuters on work trips disembark before reaching Singapore. This underscores the urgent need for strategic national projects in Johor and along the HSR corridor that could reap substantial benefits from improved connectivity to Singapore.

One such area, consistently emphasised by Emir Research, pertains to food security, where two states (Perak and Johor, due to their sizeable waqf land currently being underutilised) appear to be well-positioned to assume the role of Malaysia’s “Jelapang Sekuriti Makanan” – a scenario that could be significantly facilitated and amplified by HSR.

Additionally, Emir Research has suggested, as one of the key initiatives under the Malaysian Food Security Framework, the establishment of an AgriTech Valley/City as an AgriTech innovation cluster/hub to provide a nurturing business ecosystem and engender local and international collaboration for research and development of advanced scientific food security systems. The site in Johor appears compelling as a strategic location between Singapore and Nusantara.

Quantum tech innovation hubs in Johor is another area to be considered, given Singapore’s recent strides in developing its National Quantum Strategy.

Overall, the opportunities are plenty. However, beyond resolving funding issues, there is an urgent need to devote more thought to how the HSR can unlock its immense potential for the benefit of many Malaysians.

The writer is the founder of Emir Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research. Comments: letters@thesundaily.com