ACCORDING to the United Nations website on indigenous people there are an estimated 476 million indigenous peoples in the world living across 90 countries.

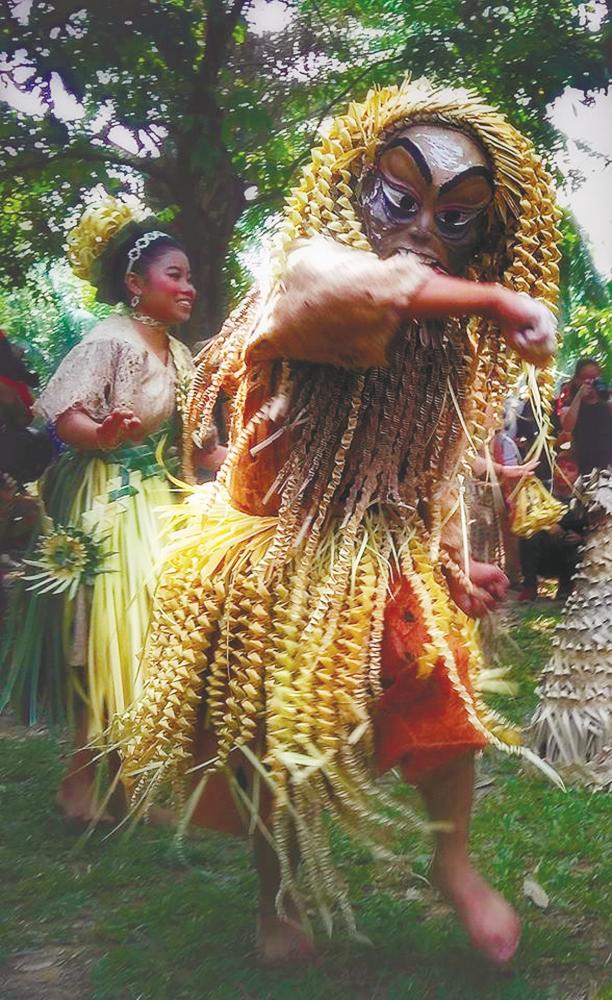

The site also says, “Indigenous peoples are inheritors and practitioners of unique cultures and ways of relating to people and the environment. They have retained social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live. Despite their cultural differences, indigenous peoples from around the world share common problems related to the protection of their rights as distinct peoples.”

The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples is commemorated on Aug 9 globally. Colin Nicholas of Centre for Orang Asli Concerns said: “[The day] is very important for indigenous people. This year celebrations will be done virtually across three different regions. There will be community programmes and cultural performances, as well as webinars.

“That day is important for indigenous people across Malaysia, the region and the world. It is a culmination of a very long struggle [over] the last 25 or 30 years to have the indigenous people recognised by the United Nations.”

In 1990, the UN General Assembly proclaimed 1993 the International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. The General Assembly followed this up with two International Decades of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: the first from 1995-2004, and the second from 2005-2014.

The goal was to strengthen international cooperation for solving problems faced by indigenous peoples in areas such as human rights, the environment, development, education, health, economic and social development.

The UN will also be celebrating the Decade of Indigenous Languages between 2022-2032, a continuation of the International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019.

“International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples is not just a way to give recognition. It is to focus on what has been done with indigenous people over the decades [and to bring] all the indigenous people together,” added Nicholas.

Malaysia’s celebrations this year will focus on the Orang Asli children.

“[Specifically] their future identity and hopes. It is not about education. It is about whether they will remain Orang Asli despite moving to the towns, getting educated, and getting regular jobs.

“Remaining Orang Asli is an issue. The basic values are not just about wearing costumes and singing songs. The core of an Orang Asli must never change.”

There will also be a webinar on early childhood management and cultural exchange among the groups.

While the culture, language and traditions of the various indigenous people of Sabah and Sarawak is celebrated regularly, not much is done to showcase the indigenous people of the Malaysian Peninsula. While there is a radio station (Radio Asyik) catering towards them, with transmissions in four major traditional languages, not much else is highlighted.

Nicholas said: “You must remember that the native peoples of Sabah and Sarawak are in the majority [in those states]. They run the government, they hold the power and they are also exploited there.

“Here in the Peninsula, the Orang Asli are a minority, making up less that 0.1%. They are a population of 215,000 now.

“In Sabah and Sarawak, not only are the individual cultures of the natives celebrated, but their land rights are also recognised to a certain extent. In the Peninsula, there is noting of the sort. The aim is to assimilate them.

“Although they say it is ‘integration into the mainstream’, the practice is actually assimilation.”

He said there were efforts to preserve the language of the Orang Asli in the 1990s and early 2000 through schools. But it was done in the form of People’s Own Language classes that we conducted after school. Though teachers initially did what they could, lack of support put an end to that.

When asked if he sees Orang Asli culture here eventually disappearing, Nicholas said: “There are many influences that will cause that to happen. At the same time, many Orang Asli became aware that when they get organised, they get exposure.

“They now use their adat, their language as the main way to fight for their rights, in particular, their lands.

“Before that they were not proud to be Orang Asli. But now they say, we have our own language, our culture, and we need to fight for our traditional lands [and] rights.”

Social media has also helped in uplifting the spirit of the Orang Asli.

“People used to call others ‘sakai’ [which is an Orang Asli ethnic group], and make all sorts of derogatory remarks. Now when that happens, the Orang Asli will attack like hell on social media.”